ROOTS OF RENEWAL

Indigenous and Local Knowledge in Restoring Degraded Lands

by Léa Lydia Lopez, BES-Net ILK Intern at UNESCO

Photo by Yohuan Cuadros from Pexels

Photo by Yohuan Cuadros from Pexels

Photo courtesy of Léa Lydia Lopez

Photo courtesy of Léa Lydia Lopez

Léa Lydia Lopez is a graduate student at the French National Museum of Natural History, where she is pursuing a master’s degree in Biodiversity, Ecology and Evolution with a specialization in Biological and Cultural diversity. She is serving as a communication intern at the BES-Net support unit on Indigenous and local knowledge led by the UNESCO’s Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (LINKS) Programme in Paris, France.

Photo courtesy of Léa Lydia Lopez

Photo courtesy of Léa Lydia Lopez

Léa Lydia Lopez is a graduate student at the French National Museum of Natural History, where she is pursuing a master’s degree in Biodiversity, Ecology and Evolution with a specialization in Biological and Cultural diversity. She is serving as a communication intern at the BES-Net support unit on Indigenous and local knowledge led by the UNESCO’s Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (LINKS) Programme in Paris, France.

Addressing land degradation and restoring degraded lands have become critical for safeguarding biodiversity and the ecosystem services essential for all life on Earth and ensuring human well-being.

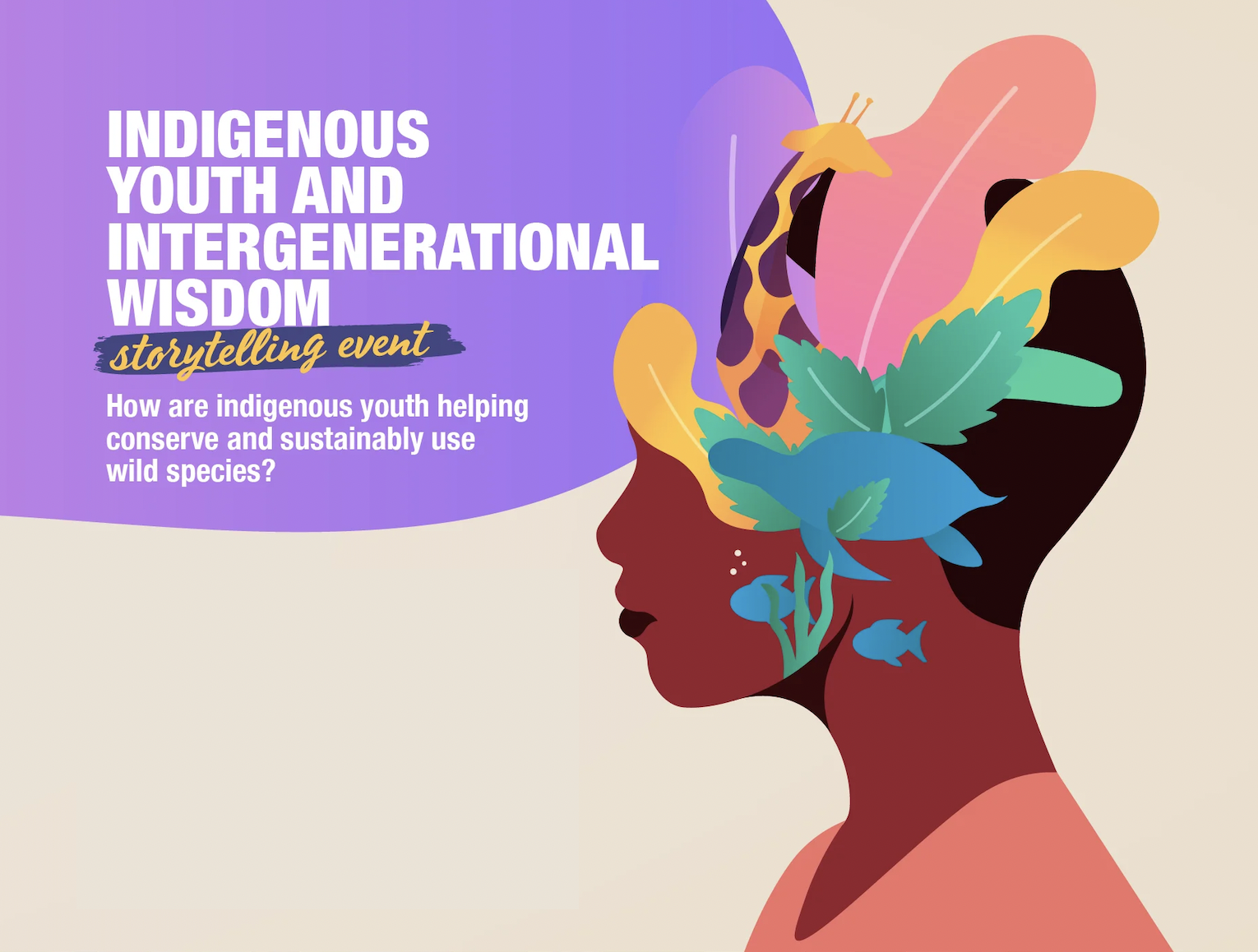

Indigenous and local knowledge on sustainable land management practices and environmental stewardship and conservation plays a vital role in preventing, reducing and reversing land degradation. Indeed, many Indigenous Peoples and local communities have ecosystem-specific knowledge on biodiversity, soil systems and water that has been tested and transmitted over generations. This knowledge is deeply embedded in sociocultural complexity, encompassing aspects such as location, language, classification systems, resource use practices, social interactions, religion, beliefs, values, rituals and spirituality that enable them to have a holistic view about a unique local environment and maintain a reciprocal relationship with nature.

Photo by FotoArtist via Canva

Photo by FotoArtist via Canva

Thanks to their continuous interaction with and dependence on nature, Indigenous Peoples are usually the first to observe and experience changes in ecosystems or biodiversity.

As environmental custodians, they are essential actors in monitoring and reporting biodiversity status and trends, including documenting historical land use changes and emerging climatic changes and impacts.

On account of their in-depth knowledge of their local ecosystems, including native species, seasonal changes and water and soil management, they have been often leading restoration efforts, tailored and adapted to local conditions and ecosystems.

Their engagement and leadership also ensure that restoration initiatives are adaptative to climate change and consider keystone species, indigenous species as well as cultural keystone species to preserve biocultural diversity and maintain ecological balance.

This is in alignment with this year’s theme of the International Day for the Environment, which focuses on land restoration, desertification and drought resilience.

This day, marked every 5th of June, presents an opportunity to highlight Indigenous and local knowledge as a foundation for coping with, halting and restoring land degradation.

Studies and environmental assessments have underscored the urgency of this issue on how Indigenous Peoples and local communities can contribute to land restoration.

Land degradation poses a severe threat to food and water security, human health and safety. The loss of agricultural productivity due to erosion, soil fertility decline, salinization and other degradation processes jeopardizes food security worldwide. Indigenous Peoples and local communities are the most vulnerable to land degradation since most of them are farmers, pastoralists, agro-pastoralists and hunter-gatherers whose primary source of income and food stability relies on natural resources and agricultural activities.

Studies and environmental assessments have underscored the urgency of this issue on how Indigenous Peoples and local communities can contribute to land restoration.

Land degradation poses a severe threat to food and water security, human health and safety. The loss of agricultural productivity due to erosion, soil fertility decline, salinization and other degradation processes jeopardizes food security worldwide. Indigenous Peoples and local communities are the most vulnerable to land degradation since most of them are farmers, pastoralists, agro-pastoralists and hunter-gatherers whose primary source of income and food stability relies on natural resources and agricultural activities.

Land degradation poses a severe threat to food and water security, human health and safety.

Land degradation poses a severe threat to food and water security, human health and safety.

With their deep understanding of agricultural adaptability and traditional farming techniques such as fallow cultivation, crop rotation, agroforestry, polyculture, terracing, innovative practices of water management and maintaining soil fertility and reducing soil erosion, Indigenous Peoples and local communities have enhanced their adaptive capacity and coping with climatic stressors.

However, more efforts are needed to enhance land and ecosystem restoration to ensure environmental sustainability and local resilience.

A poster based on key messages from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) assessment on Land Degradation and Restoration illustrates how Indigenous and local knowledge can contribute to land restoration.

Indigenous Peoples and local communities have enhanced their adaptive capacity and coping with climatic stressors.

Indigenous Peoples and local communities have enhanced their adaptive capacity and coping with climatic stressors.

With their deep understanding of agricultural adaptability and traditional farming techniques such as fallow cultivation, crop rotation, agroforestry, polyculture, terracing, innovative practices of water management and maintaining soil fertility and reducing soil erosion, Indigenous Peoples and local communities have enhanced their adaptive capacity and coping with climatic stressors.

However, more efforts are needed to enhance land and ecosystem restoration to ensure environmental sustainability and local resilience.

A poster based on key messages from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) assessment on Land Degradation and Restoration illustrates how Indigenous and local knowledge can contribute to land restoration.

Image by Sasin Tipchai from Pixabay

Image by Sasin Tipchai from Pixabay

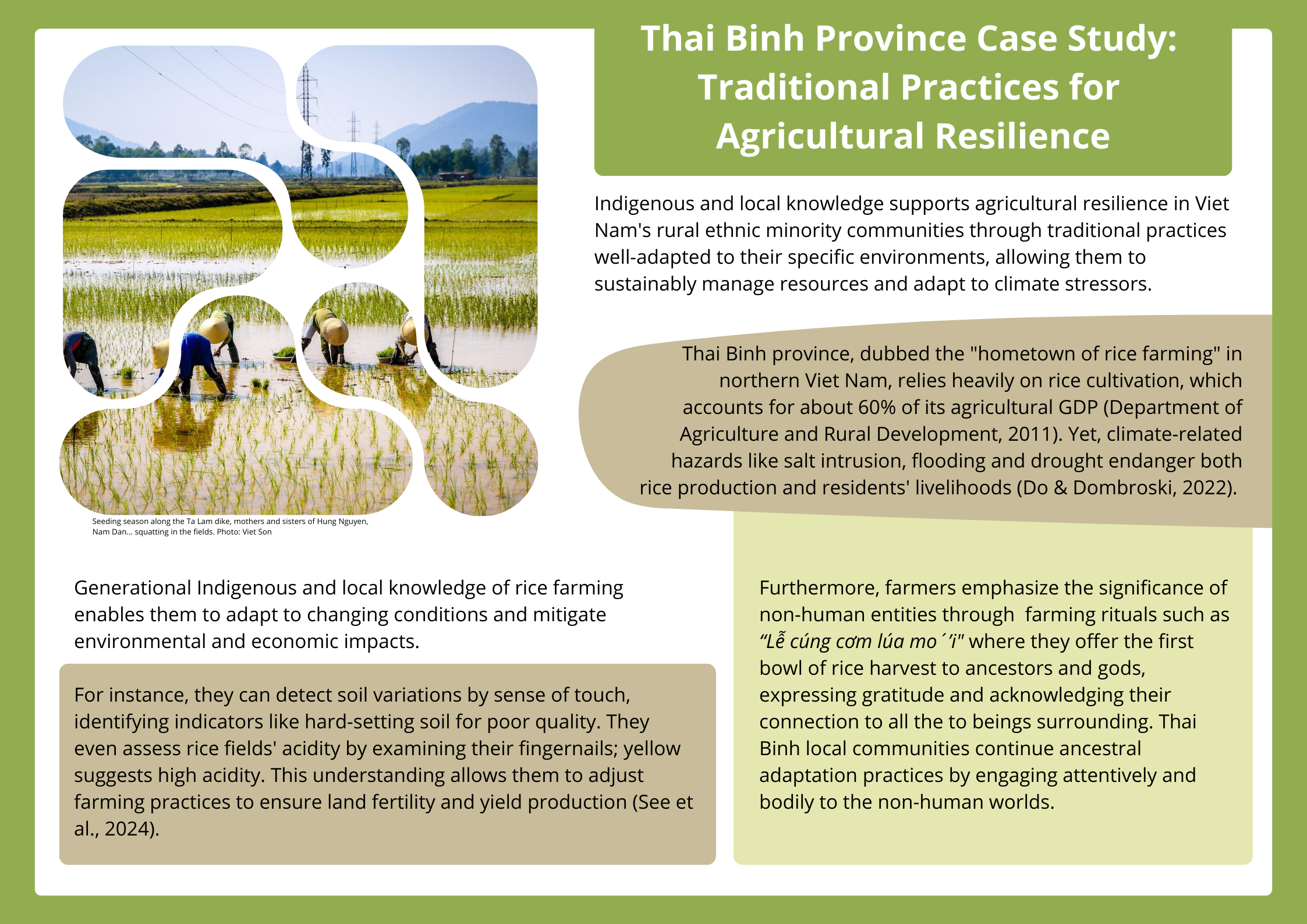

More examples show how Indigenous and local knowledge supports agricultural resilience in Thai Binh province in Viet Nam...

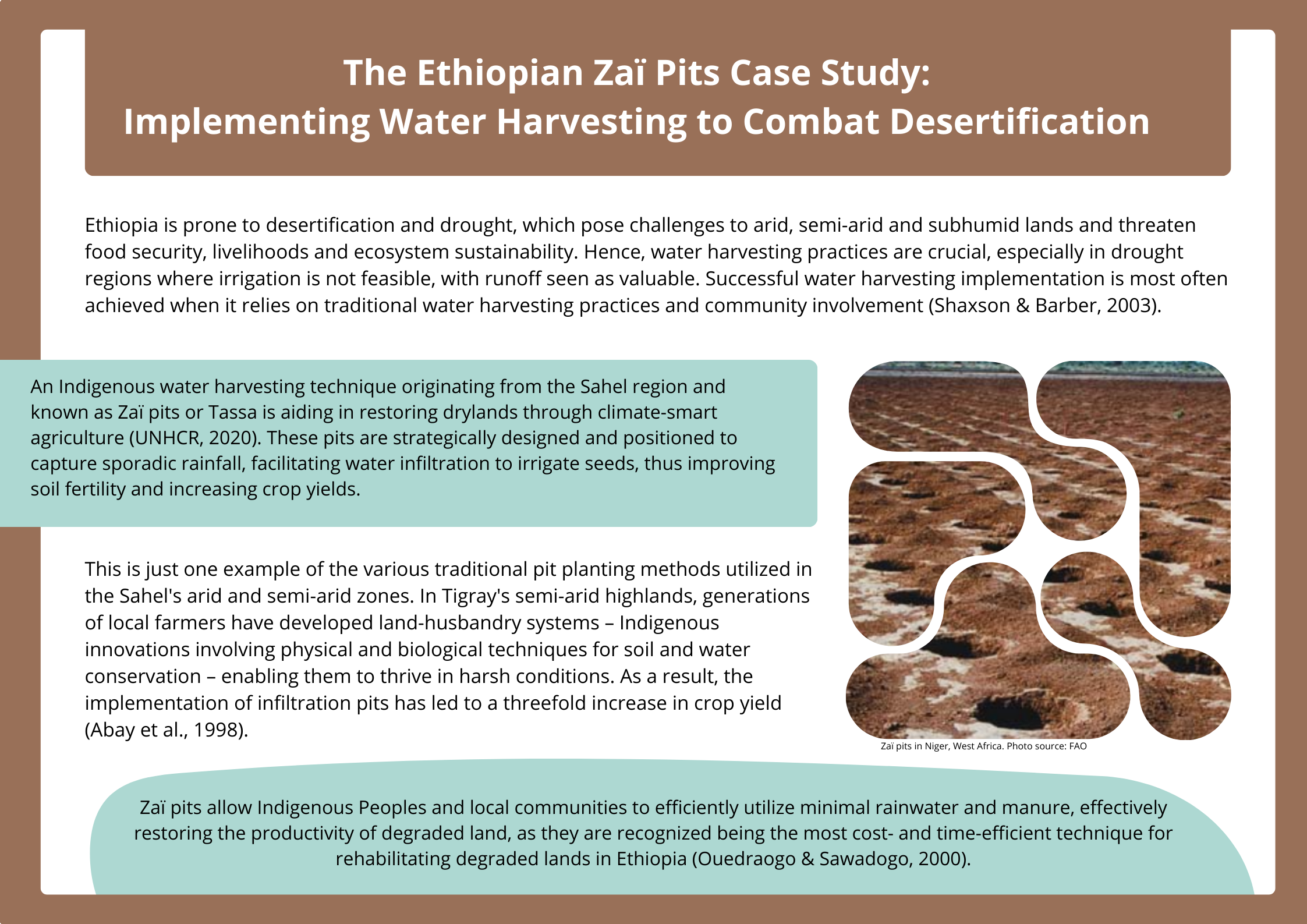

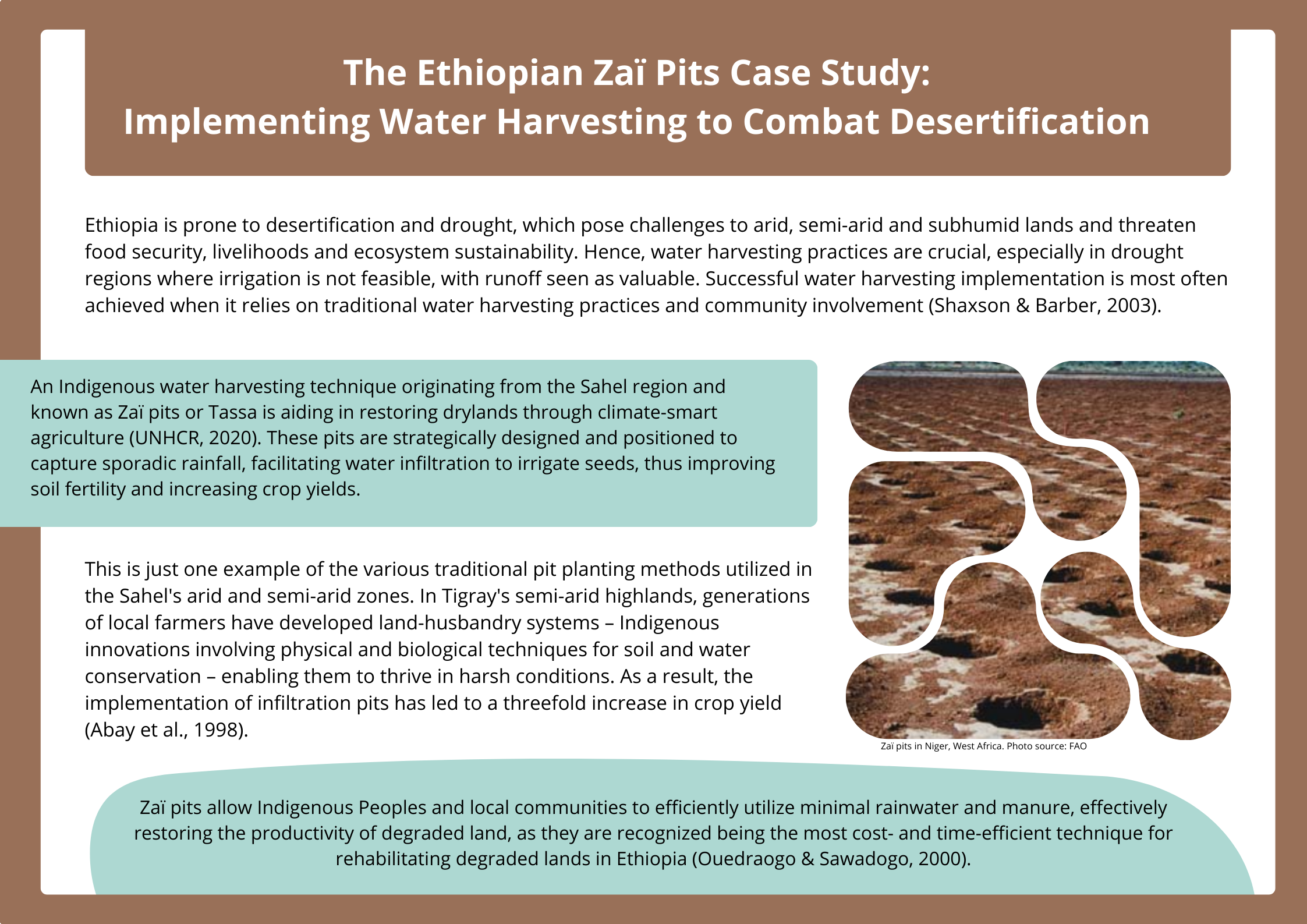

...how an Indigenous water harvesting technique, known as Zaï pits, is used in Ethiopia...

...how an Indigenous water harvesting technique, known as Zaï pits, is used in Ethiopia...

Photo by Moti Abebe on Unsplash

Photo by Moti Abebe on Unsplash

There is a growing interest in understanding how Indigenous and local knowledge shapes land users' responses to degradation, as evidenced by scientists collaborating with farmers in knowledge co-production and co-innovation processes.

Weaving scientific knowledge and Indigenous and local knowledge presents a high potential to transform climate policies by revealing the full range of impacts of climate change particularly for those most vulnerable.

Engaging Indigenous Peoples and local communities as environmental stewards and leveraging their knowledge into ecological scientific assessments, policies and coping strategies are increasingly vital, not only to enhance conservation effectiveness but also to provide the best available knowledge to decision-makers and preserve cultural heritage.

International environmental agreements, platforms and frameworks – such as IPBES, the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework – have recognized the significant contributions and value of Indigenous and local knowledge and practices in biodiversity conservation efforts and policies.

This acknowledgment underscores the need for continued collaboration and inclusion of Indigenous and local knowledge in environmental policies and practices to ensure holistic and sustainable approaches to global challenges.

References:

Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. (2011). The report on operation of the agriculture and rural development sector in 2011, and directions and tasks for 2012 in Thai Binh province

Do, T. H., & Dombroski, K. (2022). Diverse more-than-human approaches to climate change adaptation in Thai Binh, Vietnam. In Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 1–15

Ouedraogo, A. & Sawadogo, H. (2000). Three models of extension by farmer innovators in Burkina Faso. In LEISA, 16 (2): 21-22

Shaxson, F. & Barber,R. (2003). Optimizing soil moisture for plant production: The significance of soil porosity. FAO Soil Bulletin, n°79

See, J., Cuaton, G.P. & all (2024). From absences to emergences: Foregrounding traditional and Indigenous climate change adaptation knowledges and practices from Fiji, Vietnam and the Philippines. In World Development, Volume 176

UNHCR (2020). Indigenous Peoples’ Knowledge and Climate Adaptation, Fact Sheet, International Indigenous Peoples´Forum on Climate Change

Vogt, N., Pinedo-Vasquez, M. & all. (2016). Local ecological knowledge and incremental adaptation to changing flood patterns in the Amazon delta. In Sustain Sci, 11:611–623