THE FUTURE OF

BIODIVERSITY FINANCING

by Saadet Müge Ülkü

Photo by Pixabay

Photo by Pixabay

As the urgency to protect ecosystems and biodiversity intensifies, determining the sources and mechanisms of funding for these efforts remains a crucial challenge in achieving a sustainable and green future.

In recent years, the global community has become increasingly attuned to the unique challenges of biodiversity finance, with its complex, multi-stakeholder structure and its demand for tools beyond traditional finance mechanisms. Bolstered by Target 19 under the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), which highlights the need for enhancing both access and availability of funding for biodiversity, the discussion on financing biodiversity has undergone a decisive shift in the last few years.

This shift has fostered a strong recognition of the importance of making biodiversity projects more flexible in response to the unique challenges of diverse players. In biodiversity finance, this recognition has led to the exploration and integration of innovative tools and mechanisms, alongside the enhancement of existing ones, to better meet project needs. Consequently, biodiversity finance has evolved beyond traditional approaches to include a diverse array of tailored solutions for various conservation needs.

As the urgency to protect ecosystems and biodiversity intensifies, determining the sources and mechanisms of funding for these efforts remains a crucial challenge in achieving a sustainable and green future.

In recent years, the global community has become increasingly attuned to the unique challenges of biodiversity finance, with its complex, multi-stakeholder structure and its demand for tools beyond traditional finance mechanisms. Bolstered by Target 19 under the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), which highlights the need for enhancing both access and availability of funding for biodiversity, the discussion on financing biodiversity has undergone a decisive shift in the last few years.

This shift has fostered a strong recognition of the importance of making biodiversity projects more flexible in response to the unique challenges of diverse players. In biodiversity finance, this recognition has led to the exploration and integration of innovative tools and mechanisms, alongside the enhancement of existing ones, to better meet project needs. Consequently, biodiversity finance has evolved beyond traditional approaches to include a diverse array of tailored solutions for various conservation needs.

Photo by Pixabay

Photo by Pixabay

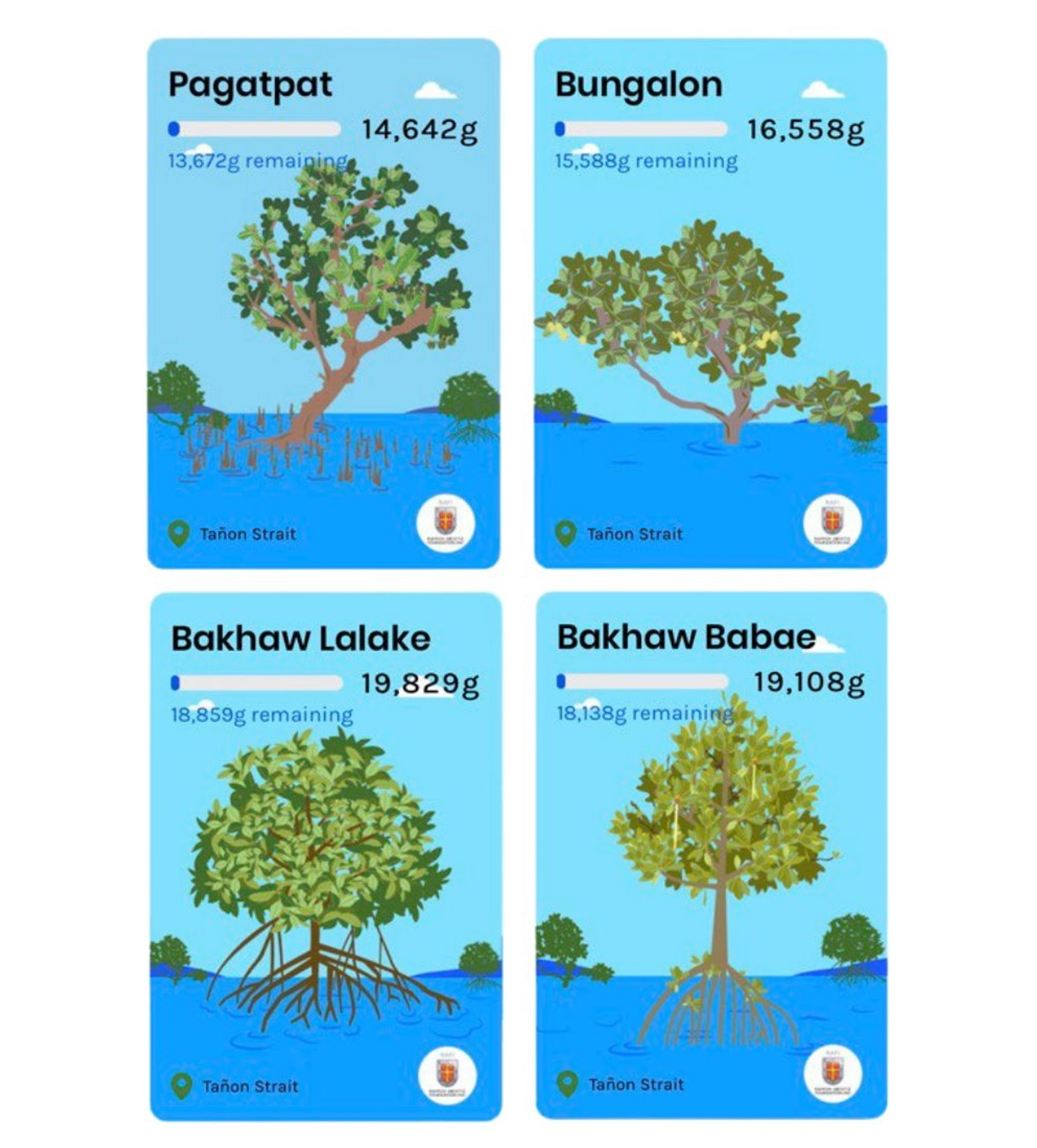

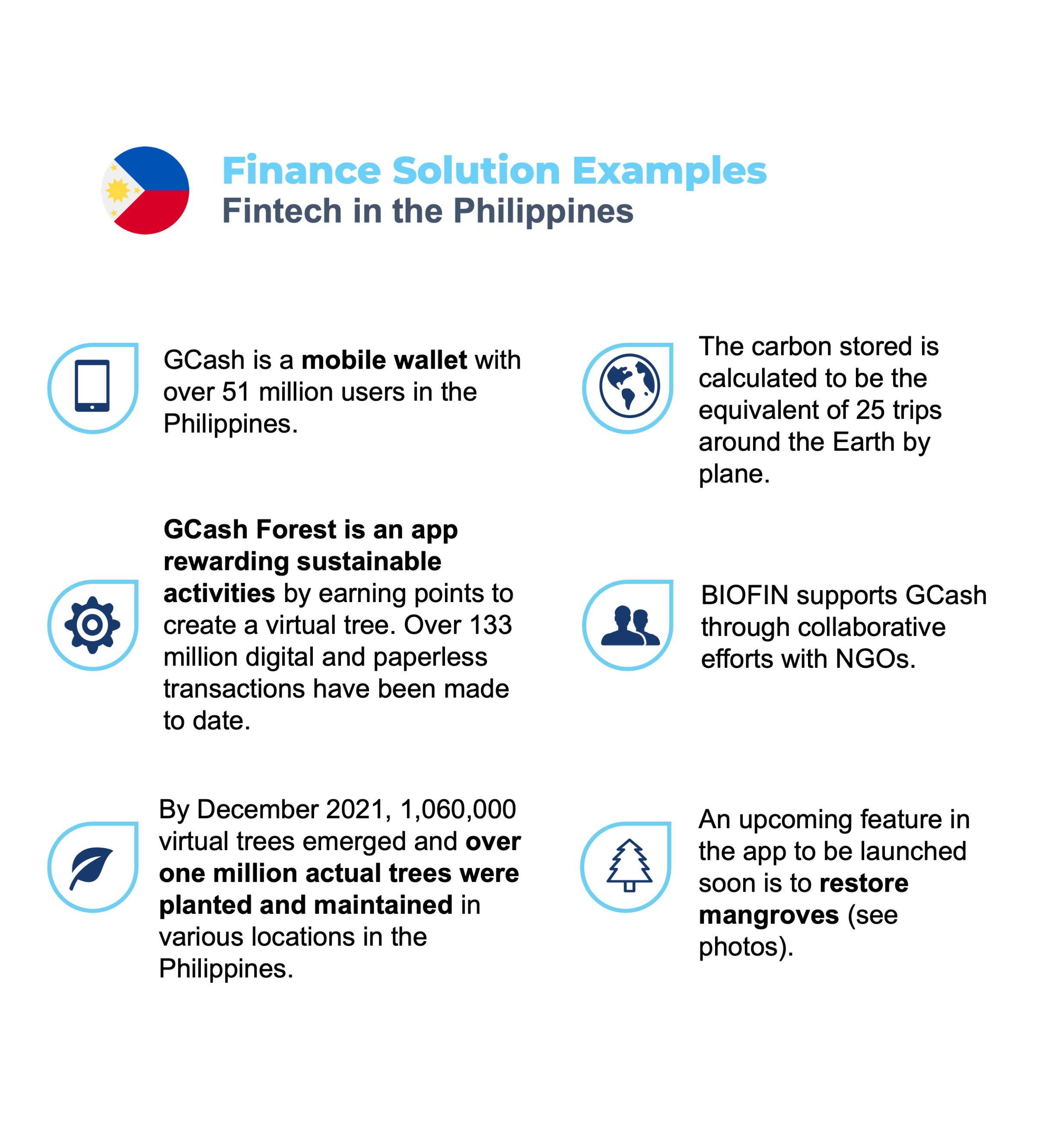

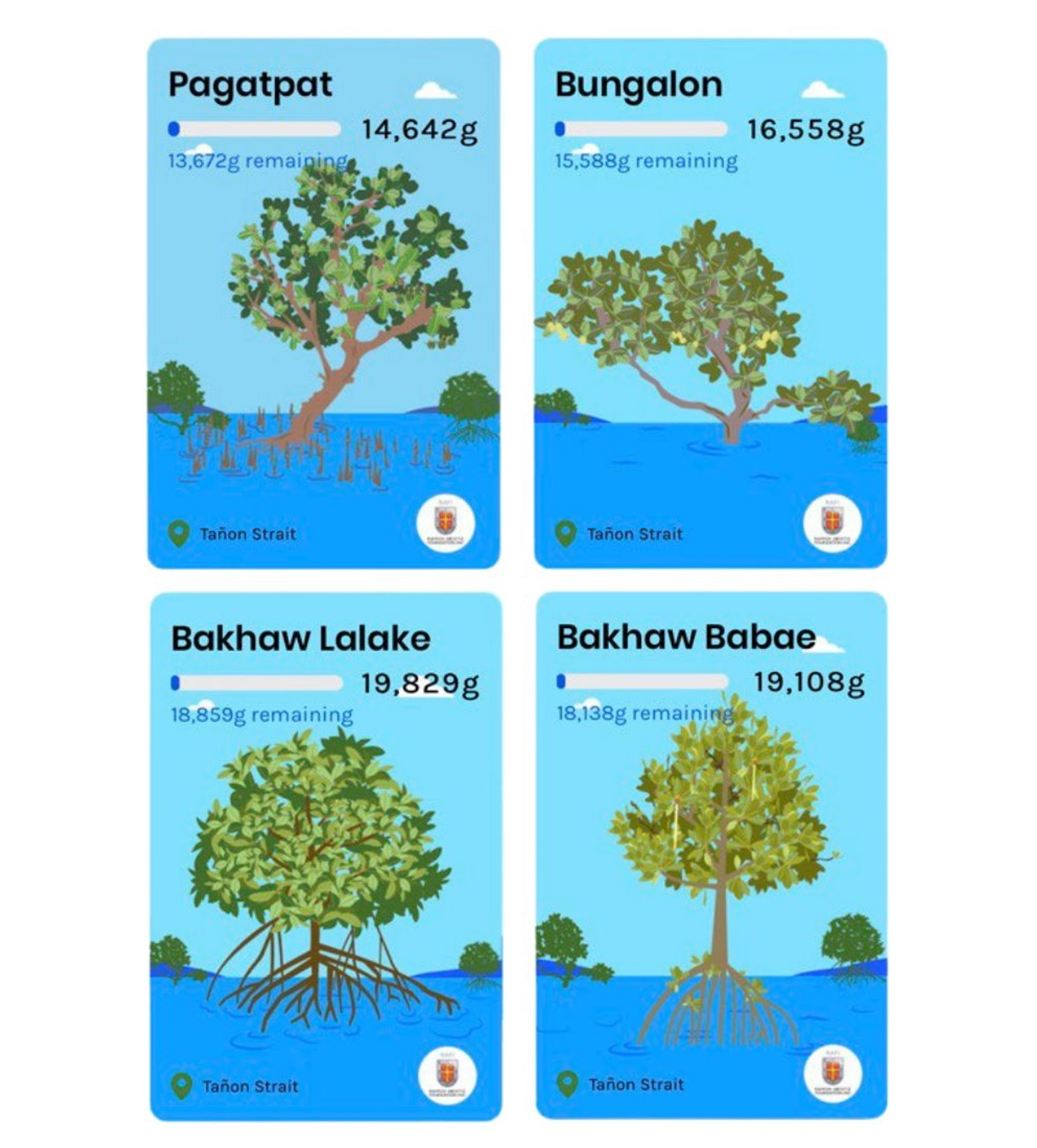

The push for innovation in biodiversity finance has been unfolding along two main lines. One significant trend is the increasing involvement of traditional capital markets and financial instruments in biodiversity finance. A prominent example of this is the GCash application, a mobile payment app in the Philippines that “gamifies” conservation. The application rewards users with tokens for engaging in sustainable activities, such as walking, using green energy or buying organic products. These tokens grow a virtual tree within the app, which is then matched by planting an actual tree in a designated area. As of 2023, GCash has planted over 2.7 million trees in 14 key areas.

The push for innovation in biodiversity finance has been unfolding along two main lines. One significant trend is the increasing involvement of traditional capital markets and financial instruments in biodiversity finance. A prominent example of this is the GCash application, a mobile payment app in the Philippines that “gamifies” conservation. The application rewards users with tokens for engaging in sustainable activities, such as walking, using green energy or buying organic products. These tokens grow a virtual tree within the app, which is then matched by planting an actual tree in a designated area. As of 2023, GCash has planted over 2.7 million trees in 14 key areas.

Animal Town is another initiative that explores apps as a source of funding for conservation. Launched in July 2024, the game allows players to learn more about conservation efforts by building and managing a tiny town of animals, completing a host of quests and interacting with endangered species virtually. It serves as a real-world test to assess whether free-to-play mobile games with in-app purchases can be a viable financing method for conservation. With almost 4.5 billion smartphone users around the world, even a tiny percentage of the users has the potential to raise momentous funds for biodiversity protection.

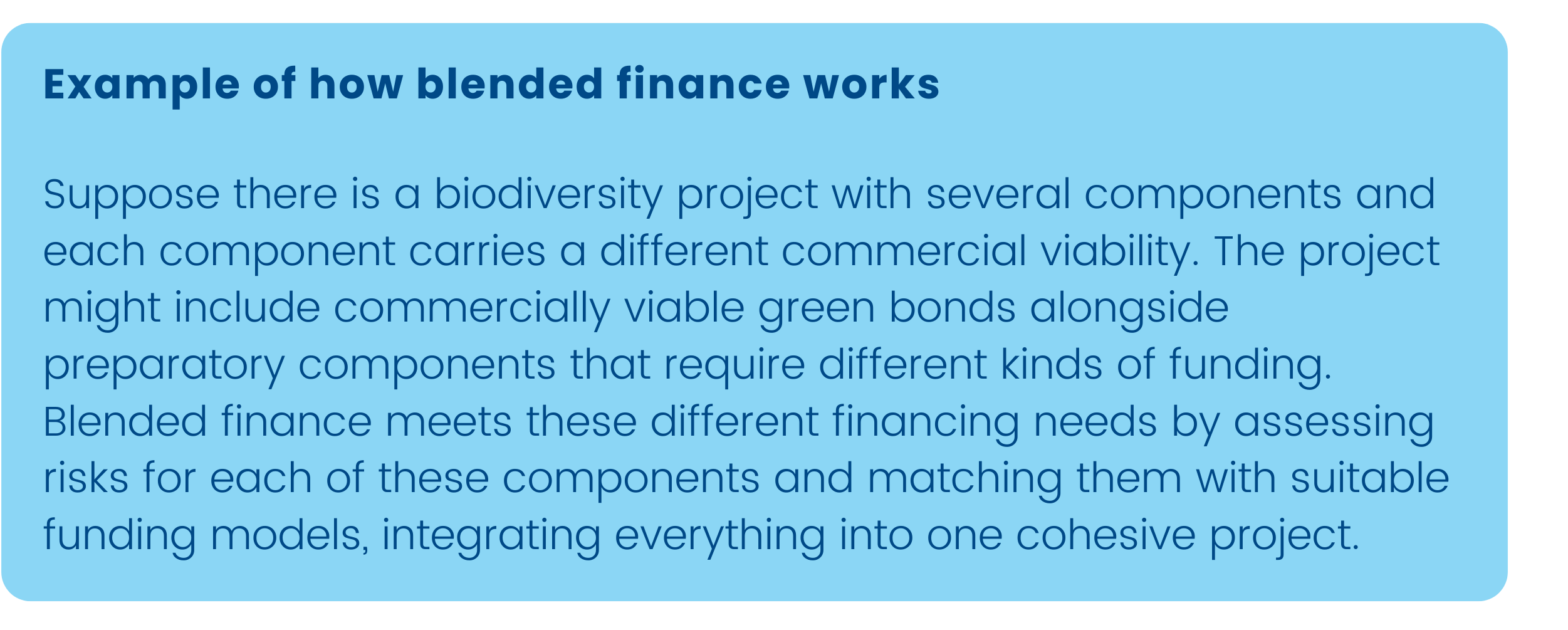

A parallel trend can be seen in the growing demand for new tools and mechanisms that could match the complex, multilevel challenge of biodiversity projects. One rising example is blended finance – an approach that utilizes development finance or philanthropic funds to attract additional funding or private investment to reduce risks.

Animal Town is another initiative that explores apps as a source of funding for conservation. Launched in July 2024, the game allows players to learn more about conservation efforts by building and managing a tiny town of animals, completing a host of quests and interacting with endangered species virtually. It serves as a real-world test to assess whether free-to-play mobile games with in-app purchases can be a viable financing method for conservation. With almost 4.5 billion smartphone users around the world, even a tiny percentage of the users has the potential to raise momentous funds for biodiversity protection.

A parallel trend can be seen in the growing demand for new tools and mechanisms that could match the complex, multilevel challenge of biodiversity projects. One rising example is blended finance – an approach that utilizes development finance or philanthropic funds to attract additional funding or private investment to reduce risks.

A number of emerging trends are also expected to play a central role in the future of biodiversity finance. Bruno Mweemba, Technical Advisor to UNDP’s Biodiversity Finance Initiative (BIOFIN) Programme, observes that the private sector’s involvement in biodiversity finance is expected to gain momentum in the coming years despite a slow start. He explains that the private sector is beginning to understand the risk of inaction on several fronts: physical risks from climate change and biodiversity loss, transitional risks from increasingly stringent regulations from governments and investors and very tangible public relations risks from failing to meet the public demand for sustainable practices.

Mweemba states, "Investing in biodiversity makes sense from a risk management point of view. It makes sense as an opportunity to tap into new avenues of funding from impact investors and it makes sense from a PR point of view because it enhances corporate reputation. It also provides companies with bragging rights over those that do not engage in these efforts."

Investing in biodiversity makes sense from a risk management point of view. It makes sense as an opportunity to tap into new avenues of funding from impact investors and it makes sense from a PR point of view because it enhances corporate reputation. It also provides companies with bragging rights over those that do not engage in these efforts.

Another promising mechanism that Mweemba highlights is public-private partnerships (or the “triple Ps”), which he believes will become a central component in how the public sector supports biodiversity conservation. He points to BIOFIN’s ongoing efforts in Zambia's Mosi-oa-Tunya National Park as an example of this. The plan involves combining green bonds with private sector involvement and collaborating with the Ministry of Finance to reinvest revenues back into the park, making it self-sustainable. This approach blends different elements of biodiversity finance – public sector financial engineering, capital market instruments and legislative aspects – capturing the complexity and enormous potential of the biodiversity finance field.

Despite these exciting new approaches, Mweemba foresees that traditional biodiversity finance mechanisms are here to stay. He notes that the use of traditional capital markets and market instruments – what he calls “green financial engineering” – enables those with a background in corporate and project finance to apply their skills for biodiversity, creating new opportunities for both the sector and the individuals involved.

On the other hand, Ronja Fischer, a Research Assistant with the BIOFIN Programme, points out several issues across financing mechanisms (such as high transaction costs from traditional hierarchical project structures) and bottlenecks in getting funds to those doing the actual conservation work in the field. Fischer is also sceptical about the focus on innovative solutions alone. “I am not sure if what we need is innovative projects. I thinkwwhat we really need is a shift in how we do things to pinpoint the root causes of biodiversity loss and build more awareness on the value shifts we need to adopt as a society. This, of course, requires different actors playing together – we need the state to change certain regulations, we need the private sector to operate differently, we need civil society to call for certain actions and we need individual actions to change in line with it. So, I think the innovative solution here would be all of us trying to work together to achieve this value shift. But that would require 100 projects, not one single innovative project.”

The future of biodiversity financing is still being decided. Ultimately, its success will lie in its adaptability to project needs, its capacity to leverage both traditional and innovative tools and its competence in fostering collaboration across sectors and regions. As the global community joins in a more coordinated effort to protect ecosystems, the push to mix traditional finance methods with innovative tools like blended finance will have to be accompanied by a wave of equally innovative policies, private sector practices and a fundamental shift in how societies interact with nature.

What we really need is a shift in how we do things to pinpoint the root causes of biodiversity loss and build more awareness on the value shifts we need to adopt as a society. This, of course, requires different actors playing together – we need the state to change certain regulations, we need the private sector to operate differently, we need civil society to call for certain actions and we need individual actions to change in line with it.

A number of emerging trends are also expected to play a central role in the future of biodiversity finance. Bruno Mweemba, Technical Advisor to UNDP’s Biodiversity Finance Initiative (BIOFIN) Programme, observes that the private sector’s involvement in biodiversity finance is expected to gain momentum in the coming years despite a slow start. He explains that the private sector is beginning to understand the risk of inaction on several fronts: physical risks from climate change and biodiversity loss, transitional risks from increasingly stringent regulations from governments and investors and very tangible public relations risks from failing to meet the public demand for sustainable practices.

Mweemba states, "Investing in biodiversity makes sense from a risk management point of view. It makes sense as an opportunity to tap into new avenues of funding from impact investors and it makes sense from a PR point of view because it enhances corporate reputation. It also provides companies with bragging rights over those that do not engage in these efforts."

Another promising mechanism that Mweemba highlights is public-private partnerships (or the “triple Ps”), which he believes will become a central component in how the public sector supports biodiversity conservation. He points to BIOFIN’s ongoing efforts in Zambia's Mosi-oa-Tunya National Park as an example of this. The plan involves combining green bonds with private sector involvement and collaborating with the Ministry of Finance to reinvest revenues back into the park, making it self-sustainable. This approach blends different elements of biodiversity finance – public sector financial engineering, capital market instruments and legislative aspects – capturing the complexity and enormous potential of the biodiversity finance field.

Despite these exciting new approaches, Mweemba foresees that traditional biodiversity finance mechanisms are here to stay. He notes that the use of traditional capital markets and market instruments – what he calls “green financial engineering” – enables those with a background in corporate and project finance to apply their skills for biodiversity, creating new opportunities for both the sector and the individuals involved.

Investing in biodiversity makes sense from a risk management point of view. It makes sense as an opportunity to tap into new avenues of funding from impact investors and it makes sense from a PR point of view because it enhances corporate reputation. It also provides companies with bragging rights over those that do not engage in these efforts.

On the other hand, Ronja Fischer, a Research Assistant with the BIOFIN Programme, points out several issues across financing mechanisms (such as high transaction costs from traditional hierarchical project structures) and bottlenecks in getting funds to those doing the actual conservation work in the field. Fischer is also sceptical about the focus on innovative solutions alone. “I am not sure if what we need is innovative projects. I think, what we really need is a shift in how we do things to pinpoint the root causes of biodiversity loss and build more awareness on the value shifts we need to adopt as a society. This, of course, requires different actors playing together – we need the state to change certain regulations, we need the private sector to operate differently, we need civil society to call for certain actions and we need individual actions to change in line with it. So, I think the innovative solution here would be all of us trying to work together to achieve this value shift. But that would require 100 projects, not one single innovative project.”

What we really need is a shift in how we do things to pinpoint the root causes of biodiversity loss and build more awareness on the value shifts we need to adopt as a society. This, of course, requires different actors playing together – we need the state to change certain regulations, we need the private sector to operate differently, we need civil society to call for certain actions and we need individual actions to change in line with it.

The future of biodiversity financing is still being decided. Ultimately, its success will lie in its adaptability to project needs, its capacity to leverage both traditional and innovative tools and its competence in fostering collaboration across sectors and regions. As the global community joins in a more coordinated effort to protect ecosystems, the push to mix traditional finance methods with innovative tools like blended finance will have to be accompanied by a wave of equally innovative policies, private sector practices and a fundamental shift in how societies interact with nature.