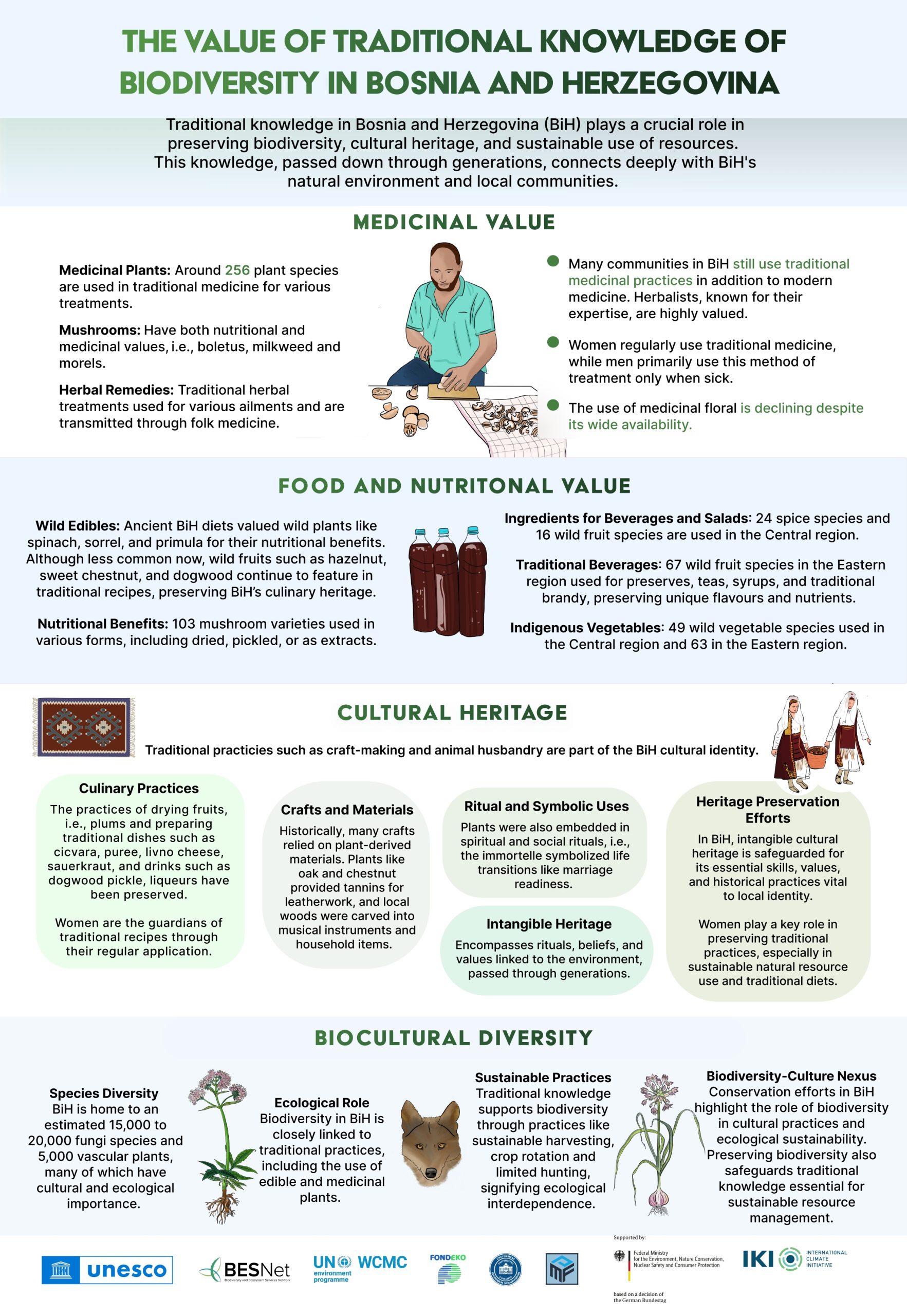

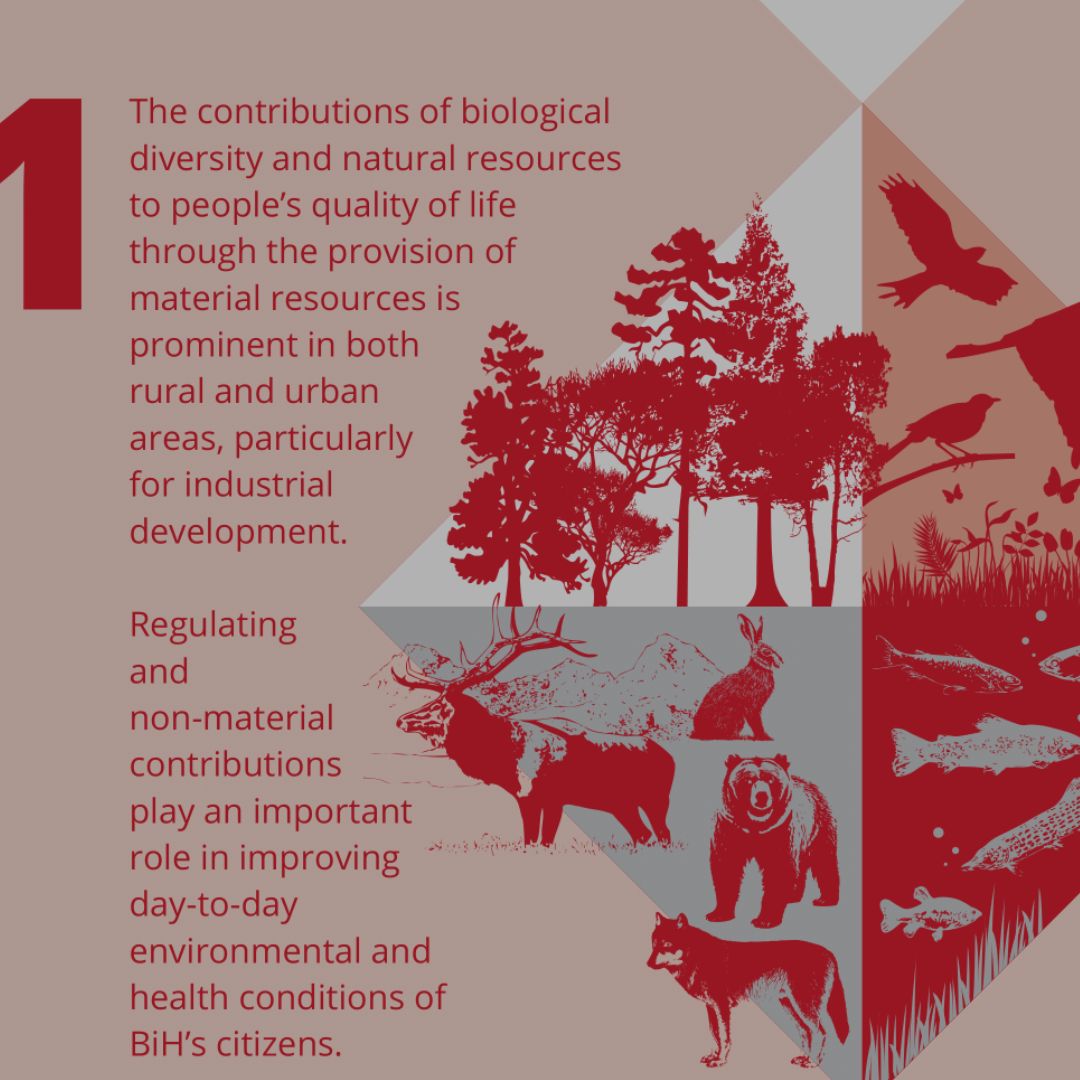

The classification of plant species as native or exotic has ramifications for how they are treated within urban green space policy and practice. Green spaces are built or managed to fulfil a range of ecological and social functions, and decisions must be made about which plants to include to achieve these functions. There is growing literary and policy emphasis on native-only planting strategies, under the assumption that native species will deliver a greater range of biodiversity benefits. Yet, there remains a disconnection between theoretical debates on the definition or value of nativeness, and urban design practice. Using a systematic review, we examine the relationship between plant nativeness and animal biodiversity in urban areas. We argue that both the use and definition of native species involve value-laden decisions. The social roots of ‘native’ definitions have led to ambiguity in its use within the literature. Despite this ambiguity, we find that most studies show a positive influence of native plants on at least one measure of biodiversity, justifying their priority in urban plantings to support native animals. We conclude with considerations for the selection of plants for urban greening to promote native biodiversity: 1) the resources a plant provides are more important than its origin, but 2) when in doubt, ‘nativeness’ is a good surrogate of whether a plant will provide for local animals, and allows for the conservation of plants themselves; and 3) flexibility in scale of provenance allows for strategic responses to changing climates or competing objectives of urban design

The role of ‘nativeness’ in urban greening to support animal biodiversity

Year: 2021