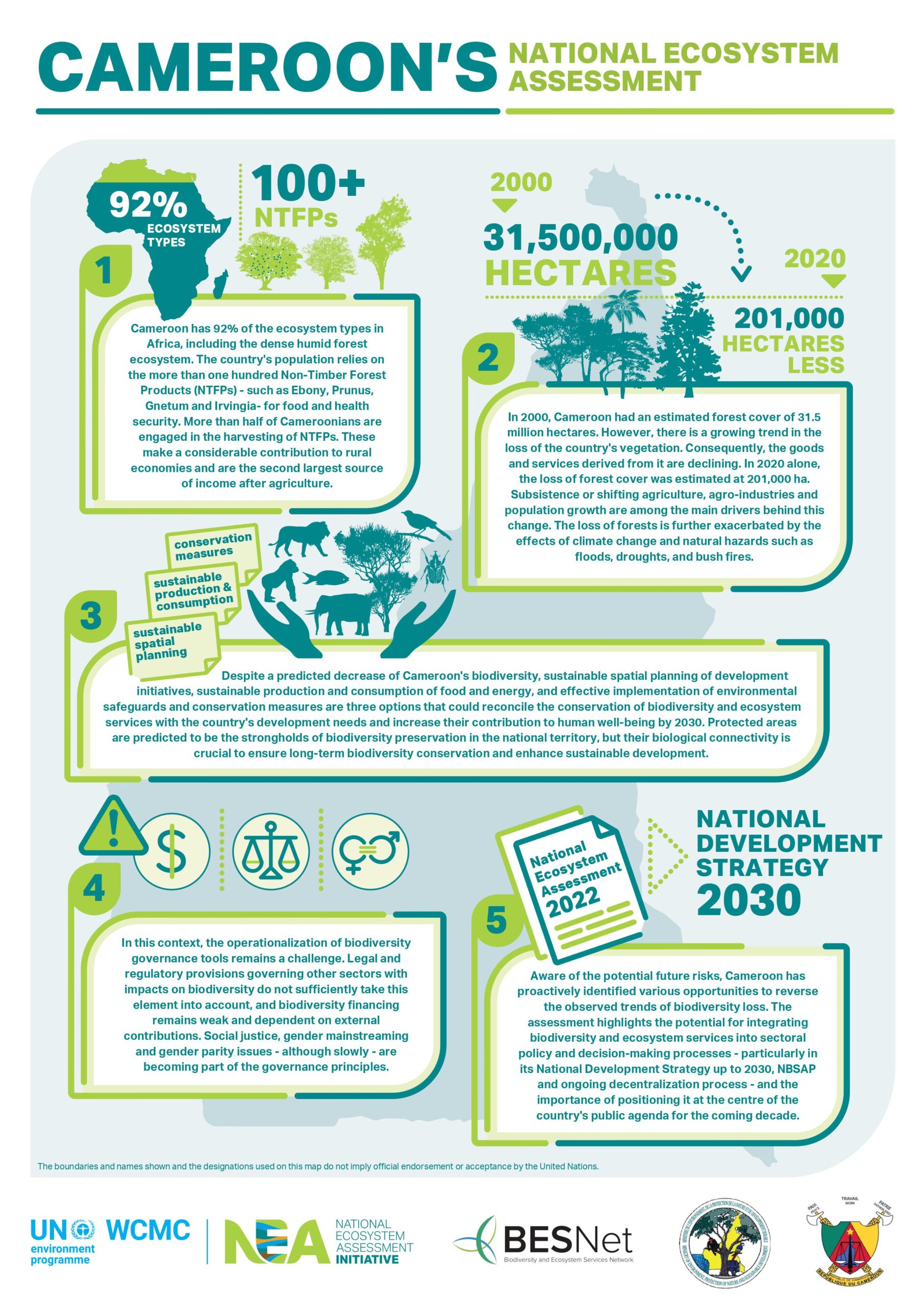

In countries new to producing ‘Manzanillo’ olive trees (Olea europaea), free cross-pollination is often insufficient to obtain high levels of fruit set. An appropriate pollination design is therefore essential to ensure a timely, abundant, and compatible pollen supply. With a view to determining whether a pollination deficit exists in a nontraditional olive area such as the northern Mexico, pollination experiments were carried out in two consecutive seasons in both a monovarietal and a multivarietal Manzanillo orchard, where Sevillano, Barouni, Picual, Pendolino, Mission, Nevadillo, and Frantoio trees were growing nearby. The pollination treatments were self-, open, and cross-pollination with ‘Barouni’ and ‘Sevillano’ pollen, the latter only in the multivarietal orchard. The results confirmed the full self-incompatible condition of ‘Manzanillo’. Open-pollination did not improve fruit set in the monovarietal orchard, but it did so significantly in the multivarietal plot, where fruit set levels under open-pollination matched those of cross-pollination. Lower pollen adhesion, as well as occasional decreased germination, and reduced and delayed pollen tube growth were observed under self-pollination, highlighting self-incompatibility reactions. The reduction in fertilization rates led to low fruit set under self-pollination. Positive effects of open- and cross-pollination treatments were also noted on fruit weight (despite higher crop loads) and pulp-to-pit ratios. A strategic plantation design, including appropriate pollinizers in the right number and position, is therefore suggested for increasing ‘Manzanillo’ fruit quality and yield in Mexico. Both ‘Barouni’ and ‘Sevillano’ served as efficient pollinizers for ‘Manzanillo’, although we recommend ‘Barouni’ as a more efficient because the bloom periods of them matched that of ‘Manzanillo’

Olive is an andromonoecious species—that is, each olive tree forms perfect hermaphrodite flowers and staminate flowers, a result of pistil abortion. Olive also exhibits strong alternate bearing, with a high flowering season (“on year”) followed by a year of light flowering and yield (“off years”) due to inhibition of flower induction caused by excessive previous crop load. Olive orchards in Spain and other Mediterranean countries are commonly monovarietal, despite the partial self-incompatibility of most olive varieties. This is possible because open, wind pollination is often sufficient to obtain adequate yield, given the extraordinary varietal richness found in most traditional olive regions, where a mixture of varieties growing nearby is common (Pinillos and Cuevas, 2009). The situation is quite different in North America. In Mexico and the United States, olive orchards often are planted in isolated areas where the amount of cross-pollen available is limited (Shemer et al., 2014). This pollination deficit frequently reduces fruit set and yield in olives (Ayerza and Coates, 2004; Navarro-Ainza and López-Carvajal, 2013; Sibbett et al., 1992). Therefore, to ensure a high yield, orchard designs including pollinizers in the correct proportion and position are required in these nontraditional olive countries. Artificial pollination is also an alternative (Sibbett et al., 1992).

If a pollination design is required, the chosen pollinizer must meet certain requirements. It must be intercompatible with the main variety, bloom at the same time, and be regular (i.e., not an alternate bearer). On a secondary level, given its main function as pollen donor, it is also convenient to select high-yielding pollinizers of high commercial value and the same purpose (table or oil) with similar crop requirements and vigor (Cuevas et al., 2001).

‘Manzanillo’ is the most important table olive in the world (Rejano et al., 2010). Unfortunately, ‘Manzanillo’ yields are not always optimal. Contradictory results regarding its degree of compatibility can be found in the literature. Some authors have reported ‘Manzanillo’ to be highly self-incompatible (SI) (Androulakis and Loupassaki, 1990; Cuevas and Polito, 1997; Griggs et al., 1975), whereas other authors label it as only partially SI, not expressing complete rejection of self-pollen but preferring cross-pollen for fertilization and hence increasing fruit set and yield under cross pollination (Dimassi et al., 1999; Lavee et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2002).

To check ‘Manzanillo’ behavior and its pollination requirements in a nontraditional olive country, such as Mexico, we designed different pollination experiments with three main aims. First, to determine whether a pollination deficit exists in monovarietal Manzanillo orchards, establishing the level of self-incompatibility exhibited. Second, to compare ‘Manzanillo’ response to open-pollination in monovarietal vs. multivarietal orchards of this genotype. The third objective was to select a good pollinizer for ʻManzanilloʼ, comparing the performance of ‘Sevillano’ and ‘Barouni’ as pollen donors because these varieties are commonly used in Mexico and the United States for this purpose.