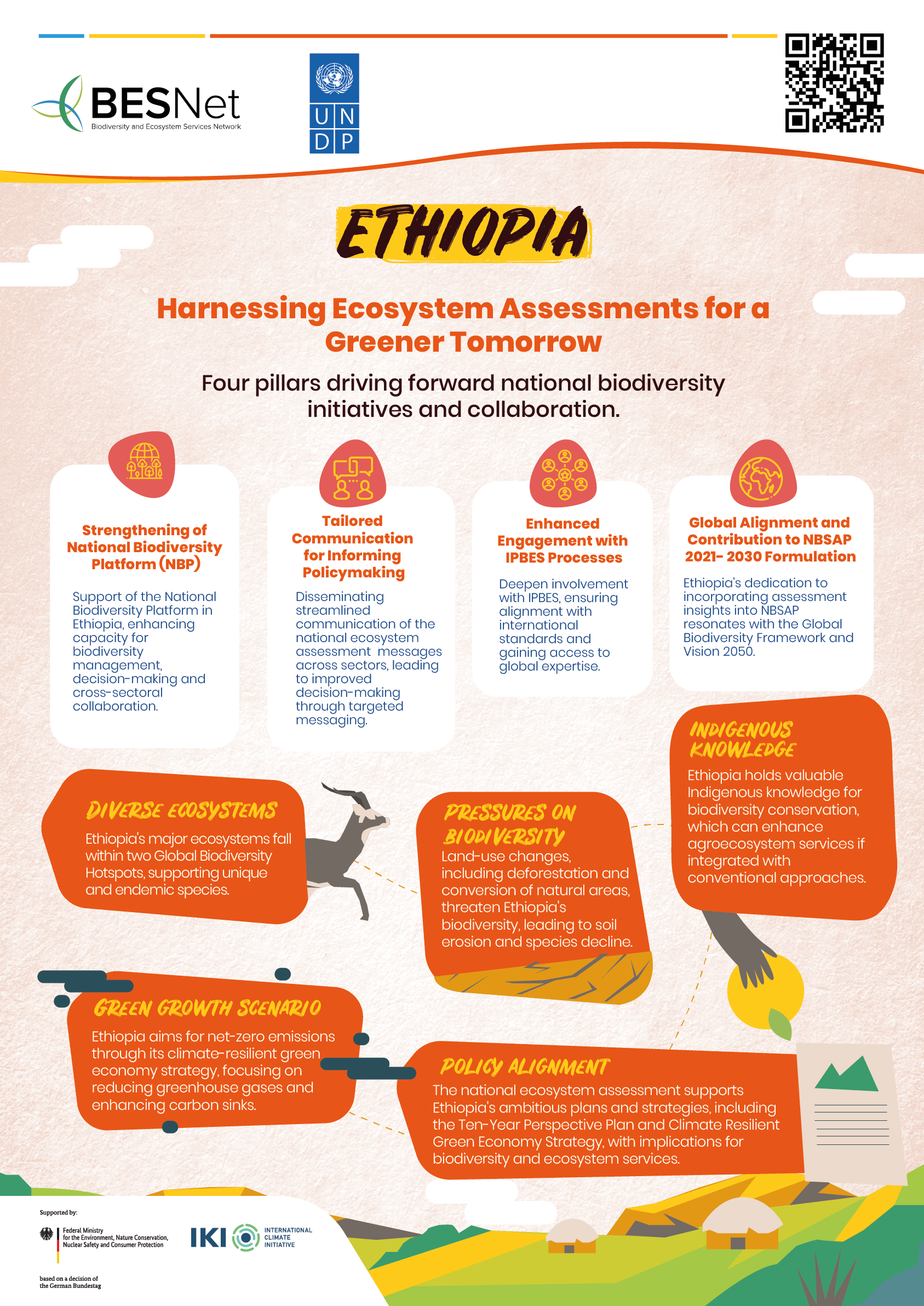

Contemporary losses of biodiversity, sometimes referred to as the sixth mass extinction, continue to mount (1, 2). A recent assessment by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) estimates that one million of approximately 10 million species that exist now are threatened with extinction along with the ecosystems they inhabit (3). Yet, in the post-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) world, investments in conservation are likely to decline further. To arrest biodiversity losses, much of the recent debate advocates two traditional approaches: Put more land under wilderness (4, 5), and mitigate drivers of change through improved governance and policies (2).

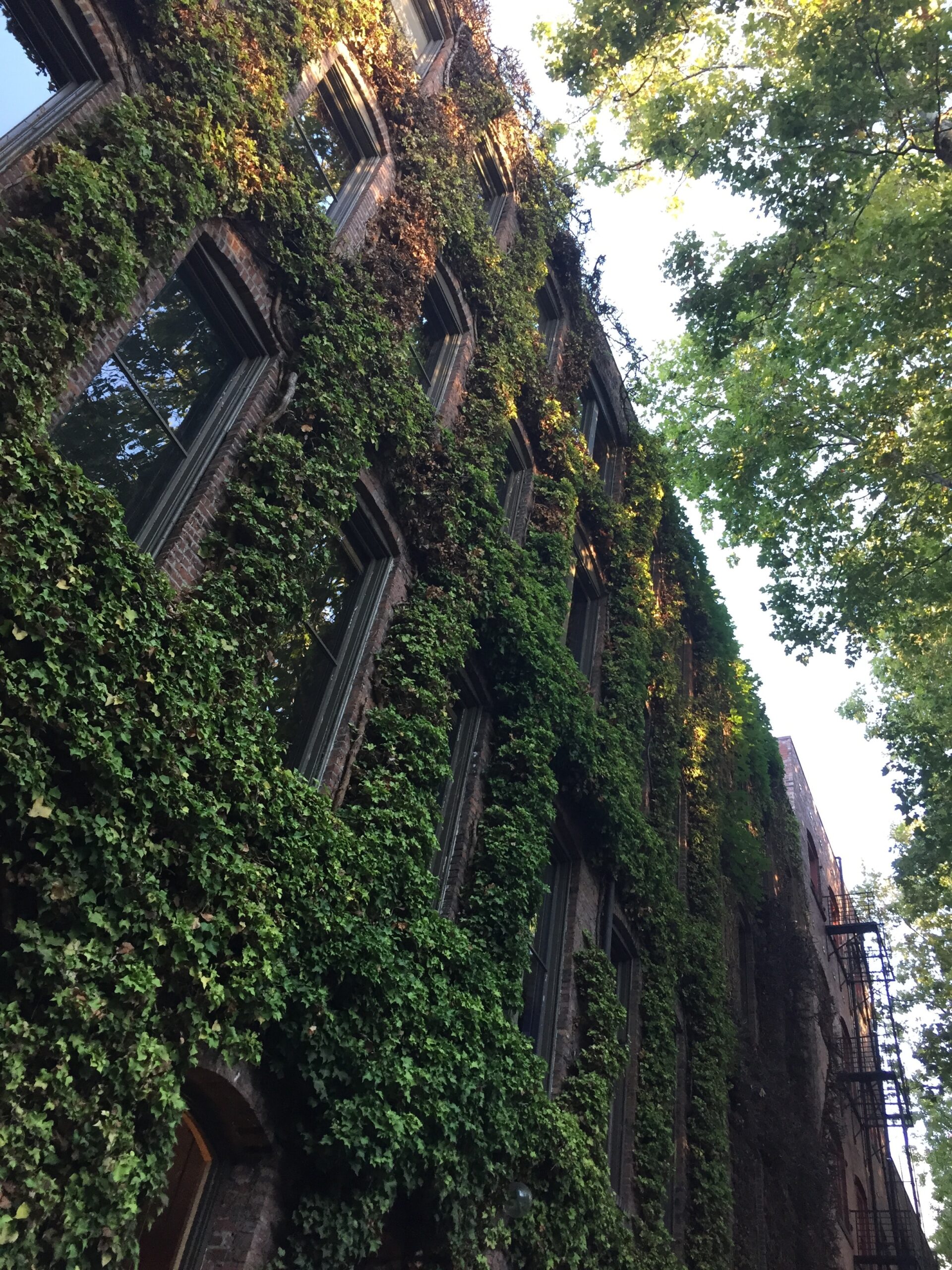

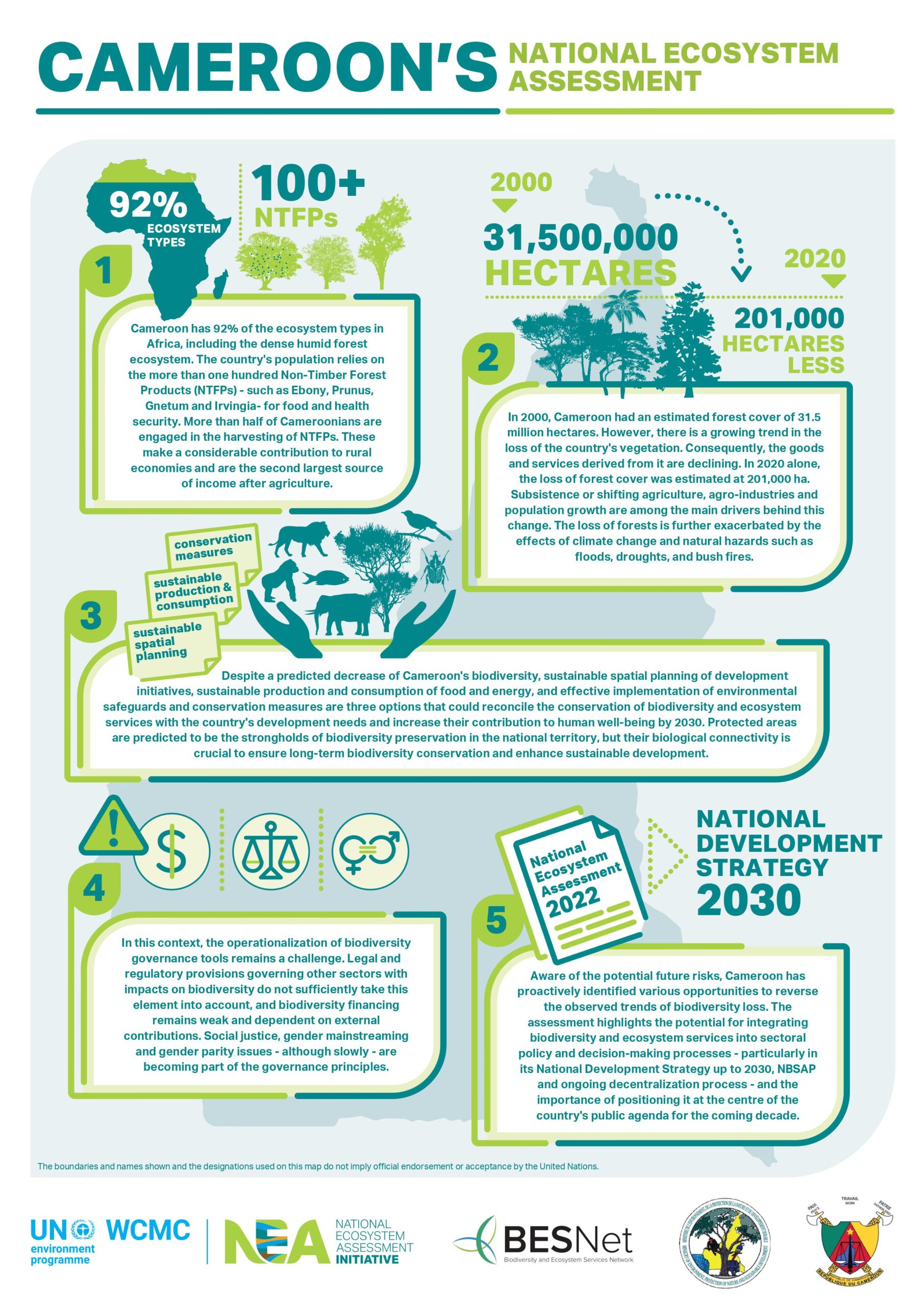

However, in the populous tropics, where most biodiversity resides, conservation of our ecosystems will remain elusive until there is a clear demonstration of the relevance of biodiversity to people’s well-being, most of whom live below the poverty line. Although nature-based solutions for addressing our most pressing challenges such as climate change, water scarcity, agricultural intensification, and health are well known (3), the link between biodiversity and human well-being has remained elusive. A major constraint, at least in the tropics, has been the lack of investment in biodiversity science that can build human resources and demonstrate the potential of biodiversity in 1) tackling climate change, natural disasters, stagnating agricultural productivity, water shortages, polluted air, and newly emerging infectious diseases such as COVID-19, 2) increasing human well-being, and 3) fostering future socioeconomic development.