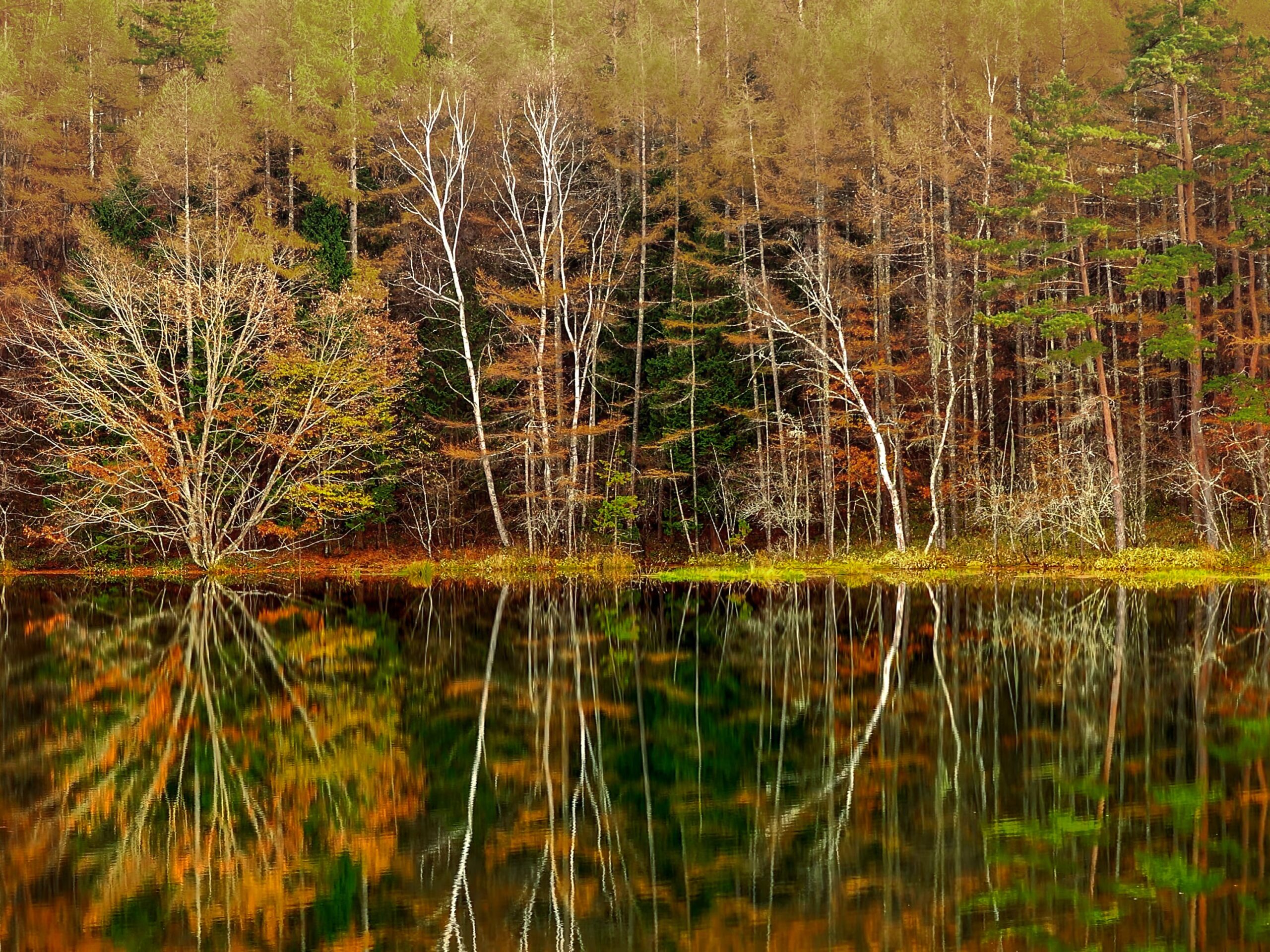

Amphibians are vital elements of ecosystems, serving as predator and prey. Their biphasic nature makes them dependent on aquatic and terrestrial habitats; as wet-skinned ectotherms, they are vulnerable to a range of environmental threats, including climate change. Yellowstone National Park (YNP) is becoming warmer and drier, and some wetlands important to amphibians have diminished. Continued climate change is predicted to reduce snowpack, soil moisture, and forest cover. We used data from models of future climate and vegetation cover to mechanistically model how climate change might affect the movements of Western Toads (Anaxyrus boreas) across the landscape of three test areas in YNP for the years 2050 and 2090, compared to 2000 as a baseline. Least-cost path analysis produced mixed results: for 2050 and 2090, physiological costs of movement increased in one test area and decreased in another; they were mixed in the third. These changes generally reflect the preference by toads for more open forests. Estimating costs for other species of YNP amphibians produced more negative results. For Columbia Spotted Frogs (Rana luteiventris) and Boreal Chorus Frogs (Pseudacris maculata) (both more aquatic and less adapted to terrestrial habitats), movement costs increased by about 2–15X. Reduced frequency or duration of rain events might limit the nocturnal movements of Western Tiger Salamanders (Ambystoma mavortium). Climate change may not have negative impacts on all amphibians throughout YNP, but increased movement costs for terrestrial habitats will accentuate effects of drying wetlands in at least parts of YNP. Land management actions that preserve habitat structure of both forest and low shrub cover may help mitigate continued drying conditions of climate change.

Modeling physiological costs to assess impacts of climate change on amphibians in Yellowstone National Park, U.S.A

Year: 2022