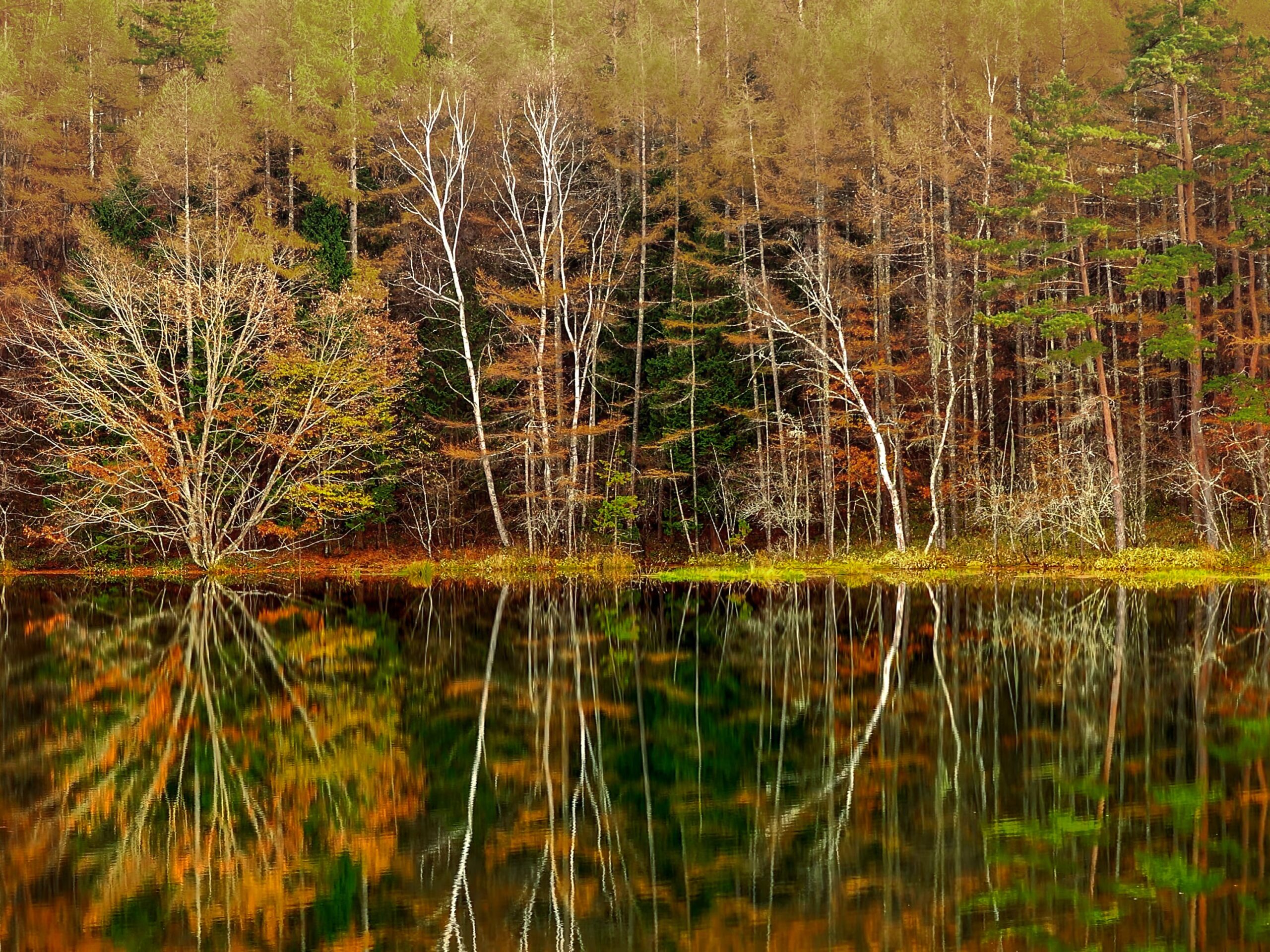

Most agroecologists value nature as much as agriculture. The idea of farming with nature rather than against her is a foundational component of how we as agroecologists think. But what do we do when the production side of agriculture puts pressure on the natural ecosystems that are being converted to farming? How do we ensure that there is enough wild nature to preserve and protect biodiversity and promote the environmental services that are important to planetary health?

This question is being asked in the Midwest of the US where natural prairies and grasslands are being plowed up to plant corn and soybeans, and most likely with large-scale monocultures dependent on industrial inputs and genetically modified varieties of both crops. When these two crops are examined from the perspective of carbon sequestration, with carbon offsets under considerable debate at policy levels, they both store a fraction of the carbon that intact grasslands do. Even more important is the realization that grasslands worldwide store about one-third of our planet’s land-based carbon. The Land Institute, based in the Midwest, has provided extensive research evidence of how efficiently perennial prairie grasses store carbon below ground with their deep and extensive root systems and argues that this natural system model of plant development should be one we use to redesign grain-based farming systems.