Expert Corner: How Do We Perceive Nature's Contributions?

by Ana Carolina Esteves Dias, IPBES Fellow for the Nexus Assessment

Image by Fabricio Macedo FGMsp from Pixabay

Image by Fabricio Macedo FGMsp from Pixabay

Dr Ana Carolina Esteves Dias is a guest expert sharing her reflections on the diverse perceptions of the values of nature based on her experience conducting participatory workshops with indigenous and local communities. Ana Carolina is a postdoctoral researcher at the Vulnerability to Viability Global Partnership, University of Waterloo, and an Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services Fellow (Nexus Assessment).

Although nature provides a myriad of benefits to people, the relationship between it and society is not always clear. Some of us struggle to understand the extent of our dependency on nature for our well-being, begging the question: what are the ways that humans perceive the contributions nature provides to us?

Human interaction with the external world relies primarily on our five senses: hearing, touch, taste, smell and sight. The contributions that nature provides to us are mediated by combinations of these senses, leading to five major pathways: experiential, extractive, observational, visual, and taste and smell.

The insights offered in this article regarding the five pathways are based on research conducted in Brazil with Caiçara communities, a traditional group whose identity connects strongly to small-scale fisheries. “Caiçara people” refers to the cultural identity of the descendants of European and African immigrants and indigenous people from Brazil. These people reflect strong cultural values of sharing and collective action, and their livelihoods include small-scale fishing, agriculture and, in the past, hunting.

1. Experiential pathway

The experiential pathway (including touch and sight) involves overall experiences people have with nature that are linked to personal experiences and feelings of well-being. For example, fishing is an activity that locals often perform in groups, requiring contributions of physical activity and inducing a sense of mindfulness, belonging and community. Physical activities such as surfing or canoeing are also included in the experiential pathway and can contribute to subjective and relational aspects of well-being.

The experiential pathway is key to maintaining certain social relations in the community and among family members. For example, a young man in the community explained, “I started fishing when I was 12, and what I like the most about it is the interaction with people such as my passed father and the gentlemen here.” Another fisher described fishing as a time to spend with parents: “I used to go fishing for squid and fish with my father and gather shellfish with my mother.” The experiential pathway also supports mental health and life satisfaction, as illustrated by an adult community member who said, “Diving, canoeing and walking in the rocks bring me peace of mind.”

A group of university students being taught ecosystem dynamics and fisheries subjects by a local fisher at Picinguaba community. © Fabiola Santos

A group of university students being taught ecosystem dynamics and fisheries subjects by a local fisher at Picinguaba community. © Fabiola Santos

The experiential pathway (including touch and sight) involves overall experiences people have with nature that are linked to personal experiences and feelings of well-being. For example, fishing is an activity that locals often perform in groups, requiring contributions of physical activity and inducing a sense of mindfulness, belonging and community. Physical activities such as surfing or canoeing are also included in the experiential pathway and can contribute to subjective and relational aspects of well-being.

The experiential pathway is key to maintaining certain social relations in the community and among family members. For example, a young man in the community explained, “I started fishing when I was 12, and what I like the most about it is the interaction with people such as my passed father and the gentlemen here.” Another fisher described fishing as a time to spend with parents: “I used to go fishing for squid and fish with my father and gather shellfish with my mother.” The experiential pathway also supports mental health and life satisfaction, as illustrated by an adult community member who said, “Diving, canoeing and walking in the rocks bring me peace of mind.”

Image captions

“Diving, canoeing and walking in the rocks bring me peace of mind.”

Kids living their childhood in close contact with nature at Picinguaba community.© Fabiola Santos

Kids living their childhood in close contact with nature at Picinguaba community.© Fabiola Santos

2. Extractive pathway

Fishers preparing the net before going out fishing at Picinguaba community. ©Fabiola Santos

Fishers preparing the net before going out fishing at Picinguaba community. ©Fabiola Santos

The extractive pathway includes dimensions of material well-being stemming from extractive activities. The harvesting of material resources such as agricultural products from the land and seafood from the ocean provides food security and income to local communities. This extractive pathway also relates to the “provisioning” category of ecosystem services established by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. However, the extractive pathway points to other important interactions, including those that are non-material. For example, fisheries and household agriculture are strong cultural components that support local cultural identity. A local expressed the importance of the cultural aspect by saying, “I enjoy fixing a fishing net, and I fish because I am used to it. I cannot go very often because of a health condition, but I feel happy to see my son going out to fish.” Another community member added, “Fisheries are a tradition; we teach our children about the culture, and fishermen like their work so much that they do not do it because of the money.”

3. Observational pathway

The observational pathway includes benefits resulting from the observation of phenomena or ecosystem functioning. These observations over time lead to local knowledge for preserving the well-being of communities in relation to natural ecosystem processes. For example, after observing over the years that native vegetation helps limit erosion in the mountain chain surrounding the communities, Caiçara people report feeling safer in areas with no deforestation. A local man explained, “The vegetation protects the river. If you remove the vegetation, the sea comes and enters the river. What sustains the sand is the jundú [sandy coastal plains] and the roots of the trees. If you clear it, the sand strip decreases.” This comment highlights how an observation shapes the recognition of the role of vegetation in preventing erosion and provides a sense of safety, thereby supporting the well-being of the observer.

Photo contest at Puruba community.

Photo contest at Puruba community.

Photo contest at Puruba community.

Photo contest at Puruba community.

4. Visual pathway

The visual pathway includes the contemplation of nature, aesthetic values and scenic views that connect people to spiritual beliefs. This pathway aligns with the subjective dimension of well-being. For instance, visual interactions with ecosystems and contemplation of nature can lead to feelings of “peace of mind”. A local woman noted, “Just the pride of looking at the seascape here makes me happy,” and a local man said, “I enjoy seeing the beach, this beauty. I open my door and look at the sea. This is my home!” Elucidation of these non-material contributions of nature is crucial for understanding the multidimensional ways people experience ecosystem services.

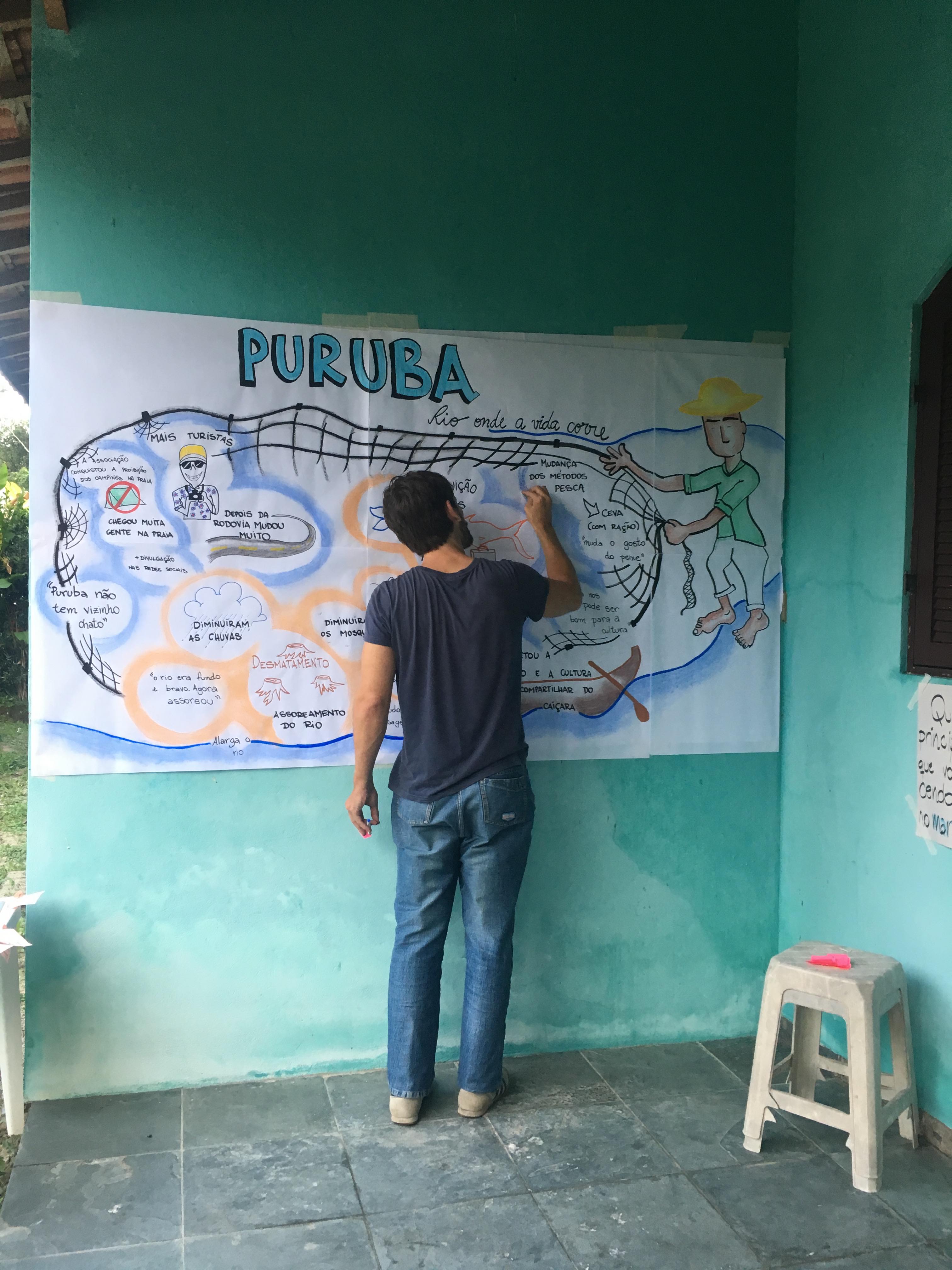

Graphic facilitation process and world café method at Puruba community.

Graphic facilitation process and world café method at Puruba community.

5. Taste and smell pathway

Finally, the pathway of taste and smell; eating good food sourced from the local environment is a pleasurable experience that fulfils nutritional needs while also connecting to social and cultural aspects of food sharing, thus connecting to community identity. The smell of food also holds the power to connect us to long-term memories, strengthening the sense of identity. Further exploration of this pathway is the next step in the research process, opening windows for new research projects in the future.

Indigenous material found in the local river and shown during the participatory workshop.

Indigenous material found in the local river and shown during the participatory workshop.

Finally, the pathway of taste and smell; eating good food sourced from the local environment is a pleasurable experience that fulfils nutritional needs while also connecting to social and cultural aspects of food sharing, thus connecting to community identity. The smell of food also holds the power to connect us to long-term memories, strengthening the sense of identity. Further exploration of this pathway is the next step in the research process, opening windows for new research projects in the future.

Indigenous material found in the local river and shown during the participatory workshop.

Indigenous material found in the local river and shown during the participatory workshop.

Overall, this five-pathway perspective provides an innovative way to understand how people value and benefit from coastal ecosystems. It also reveals linkages between people and nature that are perhaps not obvious. These linkages are, however, significant opportunities to address inequity (e.g., in the tourism sector) and reduce environmental degradation by fostering stewardship actions that consider what people value.

Acknowledgement

This work would not be possible without all the Caiçara people from Almada, Picinguaba and Puruba, Ubatuba, SP, Brazil who shared part of their rich culture in this work, colleagues from CGCommons/UNICAMP and ECGG/University of Waterloo, and guidance from supportive mentors, especially Derek Armitage, Andrew Trant, Prateep Nayak, Melissa Marschke, and Cristiana Seixas.

Photo notes

The photos in this article refer to the research carried out in three coastal communities (Almada, Puruba and Picinguaba) in Ubatuba, in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. The region has a rich history and cultural diversity, including the indigenous Caiçara and other indigenous peoples. The pictures illustrate the Photovoice activity, photo exhibition for engagement purposes and participatory workshops with graphic facilitation to understand how individuals in the communities perceived ecosystem services and well-being.

References

Dias, A. C., Armitage, D. and Trant, A. (2022). Uncovering well-being ecosystem services bundles (WEBs) under conditions of social-ecological change in Brazil. Ecology and Society, 27(1). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-13070-270144

Dias, A. C. E. (2020). Linking ecosystem services and well-being to improve coastal conservation initiatives under conditions of rapid social-ecological change. Unpublished PhD thesis. University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. http://hdl.handle.net/10012/16381

Dias, A. C. E. and D. Armitage (2021). Ecosystems, communities and canoes: Using Photovoice to understand relationships among coastal environments and social well-being in M. Gustavsson, C. White, J. Phillipson, K. Ounanian, editors. Researching People and the Sea: methodologies and traditions. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-59601-98