Expert Corner: Jean-Marc Fromentin on the Sustainable Use of Wild Species

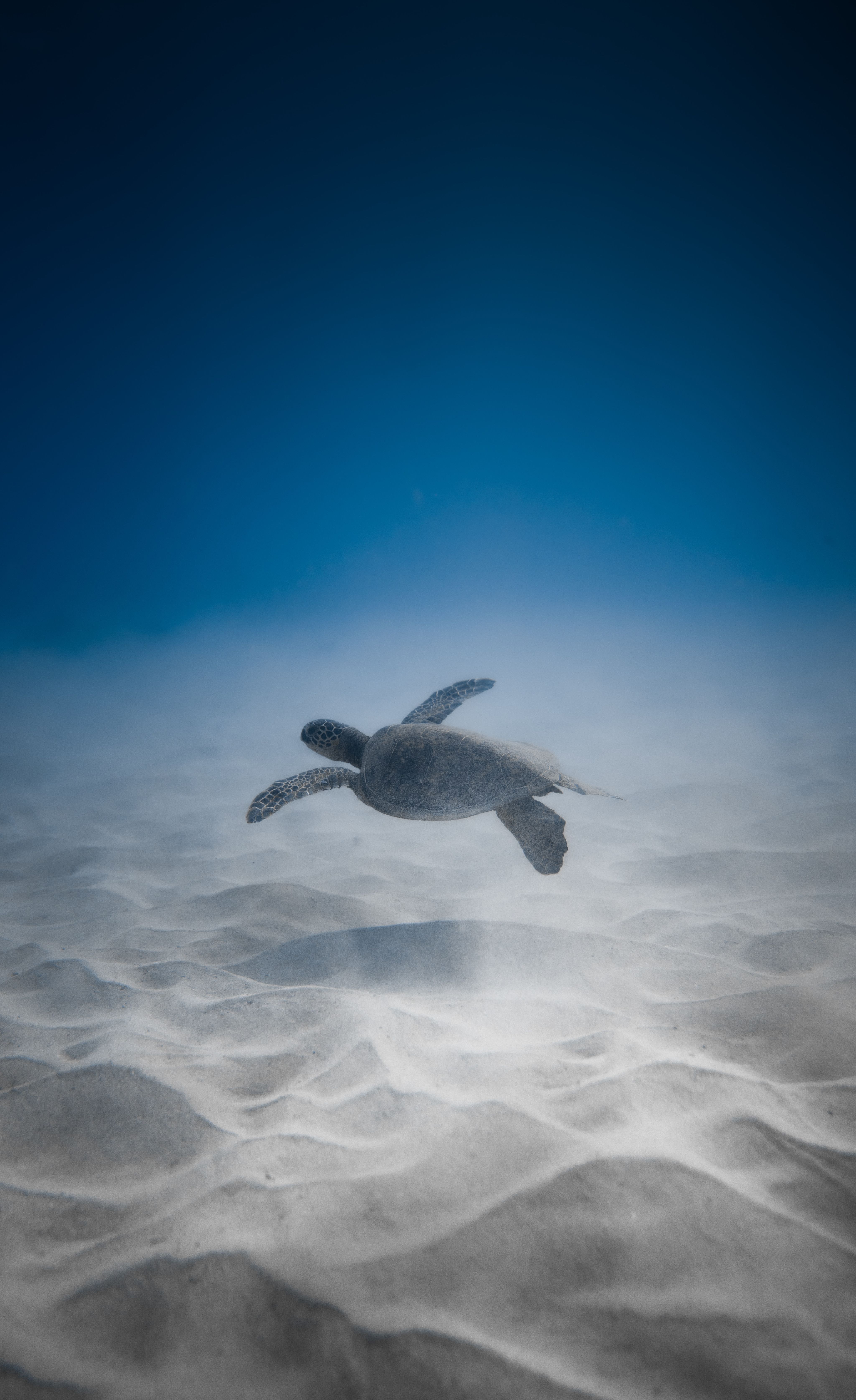

Photo by Vickholius Nugroho on Unsplash

Photo by Vickholius Nugroho on Unsplash

After a Ph.D. in marine ecology at Paris-Sorbonne University and a post-doctorate at Oslo University, Jean-Marc Fromentin (JMF) joined Ifremer in 1998 as a researcher. His research activity focuses on the impacts of environmental and anthropogenic drivers on marine populations. In parallel, JMF carried out a strong expertise activity on highly migratory fish stocks within the scientific committee of the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT). From 2000 to 2013, JMF coordinated the ICCAT Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Assessment working group, which establishes scientific advice and recommends management measures. Since 2015, JMF has been acting as the deputy director of the MARBEC Research Unit, which brings together researchers from Montpellier University, Ifremer, IRD, CNRS and INRAe working on marine biodiversity. From 2018 to 2022, JMF has co-chaired the IPBES Assessment on the Sustainable Use of Wild Species, which has been presented and adopted during the last IPBES plenary. JMF is the author or co-author of more than 100 research articles published in international scientific journals, as well as 90 scientific documents and reports.

After a Ph.D. in marine ecology at Paris-Sorbonne University and a post-doctorate at Oslo University, Jean-Marc Fromentin (JMF) joined Ifremer in 1998 as a researcher. His research activity focuses on the impacts of environmental and anthropogenic drivers on marine populations. In parallel, JMF carried out a strong expertise activity on highly migratory fish stocks within the scientific committee of the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT). From 2000 to 2013, JMF coordinated the ICCAT Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Assessment working group, which establishes scientific advice and recommends management measures. Since 2015, JMF has been acting as the deputy director of the MARBEC Research Unit, which brings together researchers from Montpellier University, Ifremer, IRD, CNRS and INRAe working on marine biodiversity. From 2018 to 2022, JMF has co-chaired the IPBES Assessment on the Sustainable Use of Wild Species, which has been presented and adopted during the last IPBES plenary. JMF is the author or co-author of more than 100 research articles published in international scientific journals, as well as 90 scientific documents and reports.

A conversation with Dr Jean-Marc Fromentin on the key messages of the Thematic Assessment on the Sustainable Use of Wild Species and its added value for decision-makers.

Wild species play a vital role in almost every person’s life, yet most of us seldom realize their crucial importance. Can you share some of the report’s messages highlighting the vital roles of wild species, especially those that may not be widely recognized?

Photo by Vickholius Nugroho on Unsplash

Photo by Vickholius Nugroho on Unsplash

One of the most striking findings from this assessment is how wide and diverse the use of wild species is all over the world. Wildlife is much more present in our daily lives than we are used to thinking. It literally touches everyone’s life in a surprisingly vast multitude of ways.

Consider that more than 50,000 wild species are used by humanity, and the practices vary a lot. Food accounts only for a fifth of the species, while other common uses include energy production, education, medicine, recreation and spiritual rituals. The report identified five broad categories of “practices” in the use of wild species: fishing, gathering, logging, terrestrial animal harvesting (including hunting) and non-extractive practices, such as observing.

While we all use wild species in one way or another, rural populations in developing countries rely disproportionally on the use of wild species for their daily life. The use of wild species is an important source of income for 1 in 5 people worldwide. Precisely because of that dependency, they do need alternative solutions to tackle unsustainable use.

Photo by Aaron Burden on Unsplash

Photo by Aaron Burden on Unsplash

Photo by Melissa Sombrerero on Pexels

Photo by Melissa Sombrerero on Pexels

The report makes it clear that the multiple benefits humanity receives from wild species are not permanent and must be protected. What are the major threats identified?

Photo by Bernard Hermant on Unsplash

Photo by Bernard Hermant on Unsplash

Photo by Timeea Pirvulescu on Unsplash

Photo by Timeea Pirvulescu on Unsplash

Photo by Atahan Demir on Pexels

Photo by Atahan Demir on Pexels

Several interconnected and mutually reinforcing threats underpin the current biodiversity crisis. Overexploitation is one of the main threats to the survival of many terrestrial and aquatic wild species.

The increase in human population and, consequently, consumption creates more pressure on wildlife. Climate change modifies wild species distributions, dynamics and interactions, increases the frequency of extreme events and impacts different regions of the world differently, raising issues of inequity for many countries. Unsustainable harvesting, including logging, fishing, gathering and hunting, contributes towards an elevated extinction risk for many wild species of sharks, rays, large mammals, trees, cacti, cycads and orchids.

That’s why sustainable practices such as management plans, selective logging and reduced impact logging are vital in order to reduce the impacts of human activities and, wherever possible, reverse these trends, resulting in better outcomes for wild species and those who depend on them.

The report provides insights, analysis and tools that inform decision-making on more sustainable use of wild species at different levels. How can we foster a science-policy-practice interface and promote constructive dialogue among these three communities to address biodiversity decline?

Photo by David Bartus on Pexels

Photo by David Bartus on Pexels

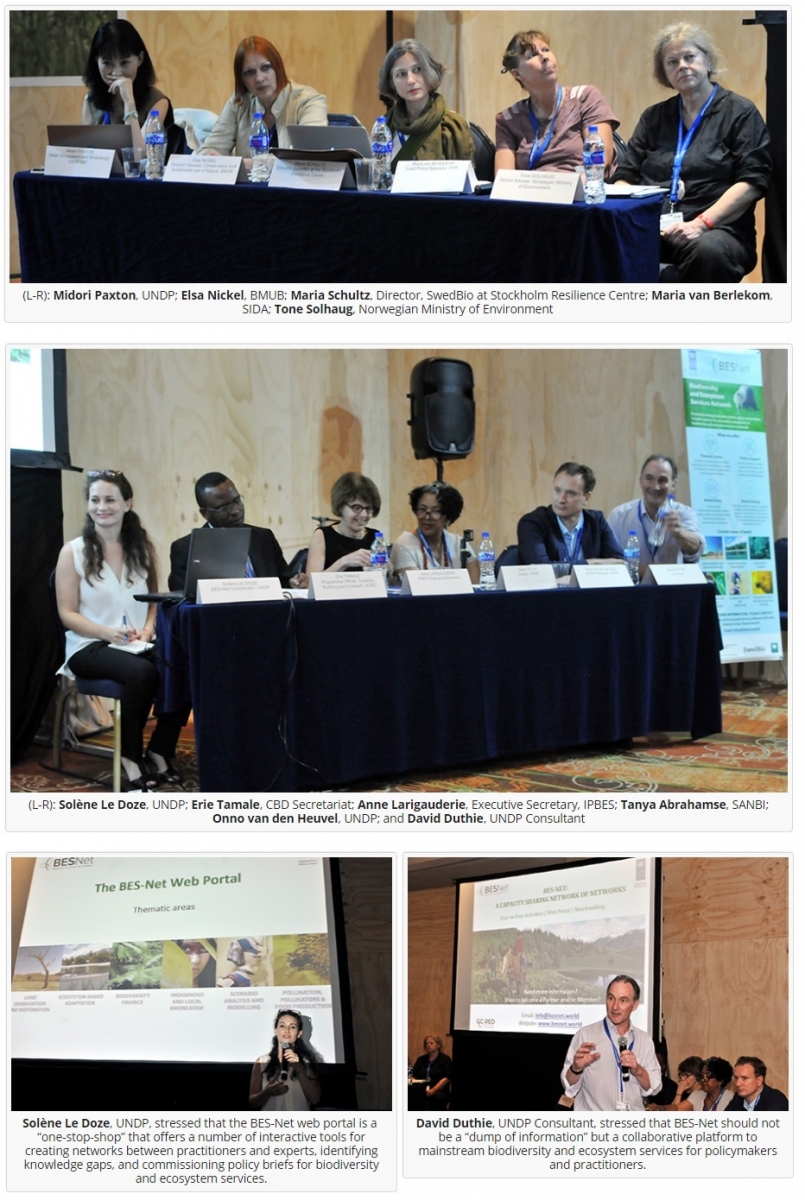

Bottom-up participatory processes that listen to the voices of local communities enable the right conditions for decision-making. The report states clearly that we have to work closely with indigenous peoples and local communities as knowledge holders. Indigenous peoples have been living in harmony with nature for centuries, sometimes millennia, so the knowledge and governance systems developed must be preserved and protected similarly to endangered species. Monitoring is also crucial to prevent species decline, and monitoring efforts that are inclusive of indigenous peoples and local communities and scientific approaches often better inform decision-making.

Transparent and effective governance systems enabling collaboration between diverse stakeholders encourage positive ecological and social outcomes. We often have big winners in the distribution of natural resources, while the most vulnerable communities pay a high price for nature’s decline. The equitable distribution of costs and benefits is a critical condition to advance policies that recognize the interconnection between the status of the well-being of people and the planet.

Finally, while it is key to have robust institutions, it is also important that they are agile and adaptive to change, as we live in a reality that often changes in unexpected ways.

What steered your interest towards the IPBES process and inspired you to join an IPBES Assessment as Co-Chair?

Photo by Nav Photography on Pexels

Photo by Nav Photography on Pexels

In my experience working as a marine biologist on bluefin tuna, I realized how overexploitation (overfishing in that case) is a multidisciplinary challenge that spans many sectors and affects communities that see the issue from diverse – yet equally valuable – perspectives. During that experience, I witnessed the power of leveraging solid scientific research to inform policies and decisions on nature.

IPBES is a critical platform that enables that link between science and policy. Thus, I was honoured to be selected as one of the Co-Chairs of the Sustainable Use Assessment.

What advice would you give to your younger self or to an early career researcher aiming at joining IPBES assessments as a fellow?

Photo by Daniel Torobekov on Pexels

Photo by Daniel Torobekov on Pexels

I would strongly recommend this experience to young researchers, as engaging with IPBES shows how academic research can address very urgent issues related to nature. It brings academic quests outside the institutions and offers intellectual rigour to the communities. At the same time, this dialogue with decision-makers and practitioners helps academics to identify blind spots in their research and see a tangible implementation of their recommendations in the real world.

So, my advice would be to apply to one of the available programmes, such as the IPBES fellowship, and to keep an eye on calls for experts on topics of interest.