Expert Corner: A Unique Coexistence of an Indigenous Tribe (Adivasi) with Tigers in the Western Ghats of India

Suggesting New Perspectives on Conservation

Photo by Prashanthns on Wikimedia Commons

Photo by Prashanthns on Wikimedia Commons

Assoc Prof Kamaljit K Sangha works as an Ecological Economist at Charles Darwin University, Australia. She works with Indigenous communities on linking ecosystem services from rainforest and savanna ecosystems with people’s well-being. Assoc Prof Sangha is the Lead Author for the upcoming IPBES Nexus Assessment and Co-Chair of the IUCN CEESP-led Local Economies, Communities and Nature Specialist group. She has published over 100 articles in various national and international journals and conference proceedings.

Dr. M. Balasubramanian is an Assistant Professor at the Centre for Ecological Economics and Natural Resources of the Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore. His main research interest is the economics of forest ecosystem services linked with human well-being, climate change and biodiversity conservation. He is also a subject reviewer of IPBES and a member and reviewer of UK Research and Innovation, International Peer Review College, London.

Dr. C. Madegowda is a Senior Researcher and Coordinator at the field station of Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment in Biligiri Rangaswamy Hills. He is from a local Indigenous tribal group and works closely with people applying community-based conservation approaches. His works include the implementation of the Forest Rights Act, 2006 and empowering Indigenous communities’ movements.

This article provides information about the Soligas, an Indian Adivasi tribe that has been coexisting with wildlife such as tigers and elephants in the Western Ghats of India for many years.

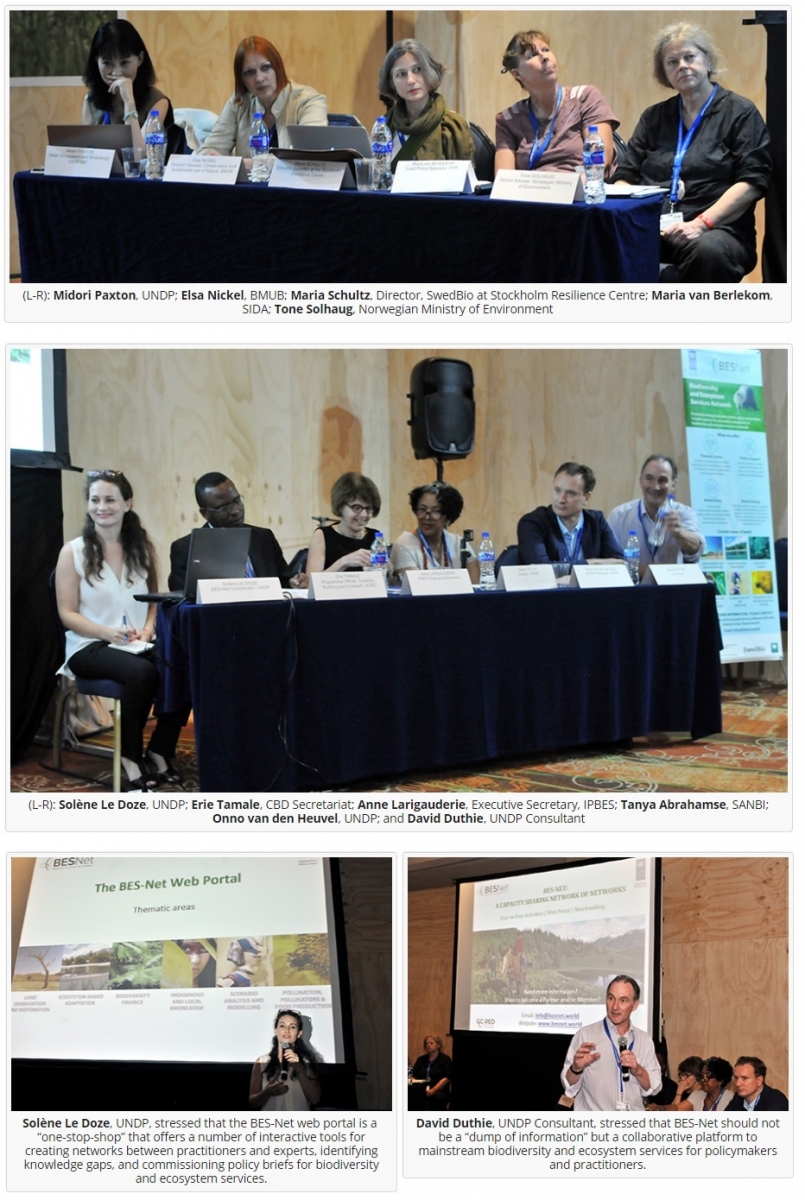

To understand people’s perspectives and their relationships with the area, the authors visited them in November 2022. They met with Dr. Madegowda, a senior researcher at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment, who guided their discussions with the community elders and provided insights.

A global biodiversity hotspot: the Western Ghats

The Western Ghats in India – along with the island of Sri Lanka – are one of the world’s 36 biodiversity hotspots, spreading over six states covering an area of around 164,280 km2 and stretching over a distance of 1,500 km. A significant feature of the Western Ghats is that they are recognized among the world’s eight “hottest hotspots” of biological diversity and were designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2012 for their exceptionally high level of biological diversity and endemism. The Indian Ghats harbour 27 national parks (five in Karnataka) and 160 wildlife sanctuaries (23 in Karnataka alone). These Ghats are home to around 6,500 flora and fauna species with a high degree of endemism.

Most importantly, the Ghats represent a living cultural landscape, meaning that people have lived with and managed the landscape with ongoing intimate relationships, including their livelihoods and religious, socioeconomic, cultural and spiritual connections.

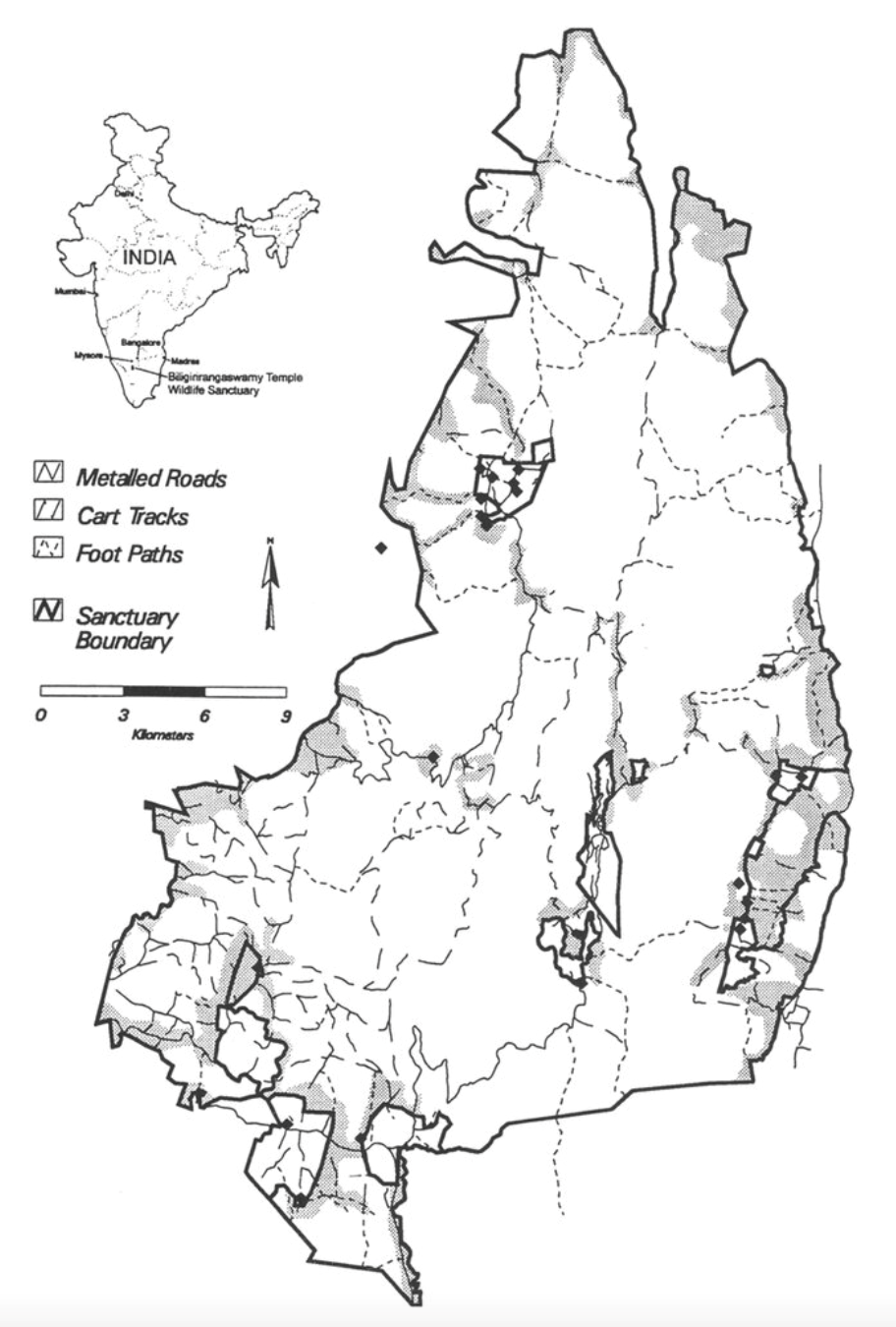

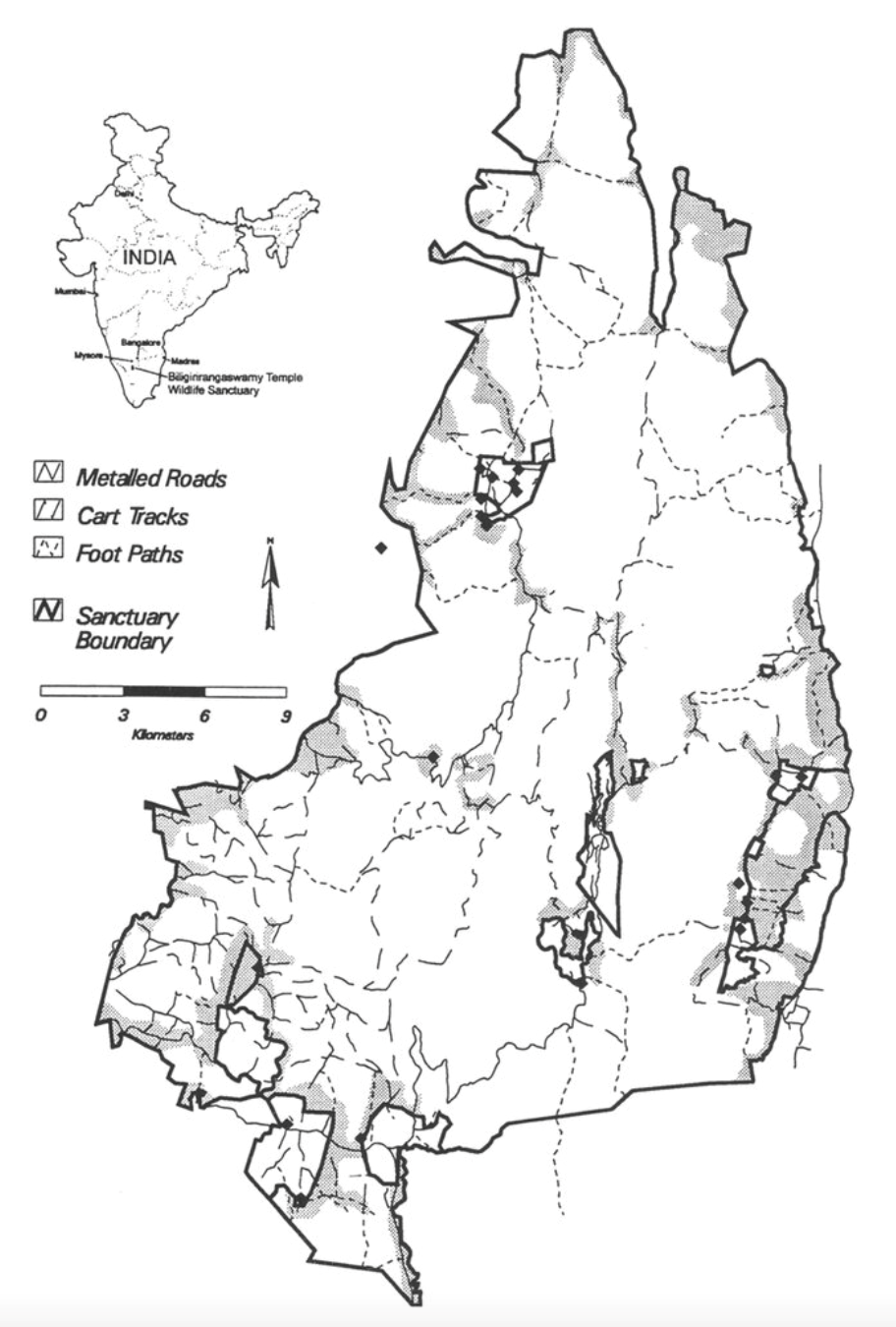

The Biligiri Rangaswamy Temple Wildlife Sanctuary (BRTWS), the study site (Figure 1), represents one of the wildlife sanctuaries located in the state of Karnataka, where Adivasi people (including the Soligas) have been living for millennia and have imbued relationships with wildlife and landscape that are connected to their cultural and spiritual beliefs.

Figure 1. Location of the BRTWS, Karnataka, India. (Source: Shankar et al. 1998)

Figure 1. Location of the BRTWS, Karnataka, India. (Source: Shankar et al. 1998)

Figure 1. Location of the BRTWS, Karnataka, India. (Source: Shankar et al. 1998)

Figure 1. Location of the BRTWS, Karnataka, India. (Source: Shankar et al. 1998)

Most importantly, the Ghats represent a living cultural landscape, meaning that people have lived with and managed the landscape with ongoing intimate relationships, including their livelihoods and religious, socioeconomic, cultural and spiritual connections.

The Biligiri Rangaswamy Temple Wildlife Sanctuary (BRTWS), the study site (Figure 1), represents one of the wildlife sanctuaries located in the state of Karnataka, where Adivasi people (including the Soligas) have been living for millennia and have imbued relationships with wildlife and landscape that are connected to their cultural and spiritual beliefs.

The Soligas: Indigenous Peoples of the Western Ghats, India

The Soligas, or Adivasi as called in India (meaning “the original inhabitants of the land”), are an Indigenous tribe believed to be among the first settlers in India. They speak the Dravidian language and practice subsistence living to date.

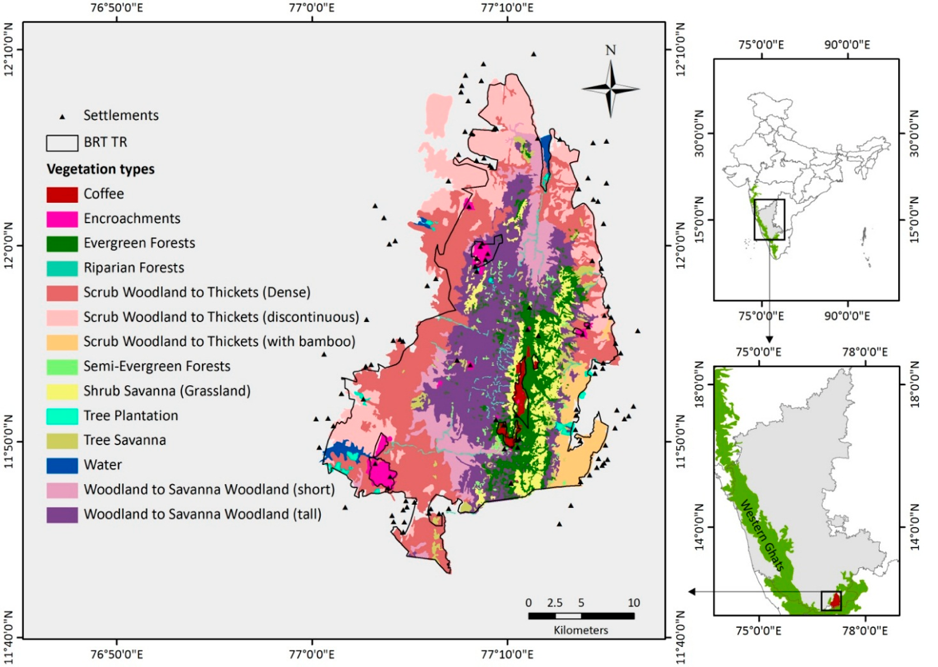

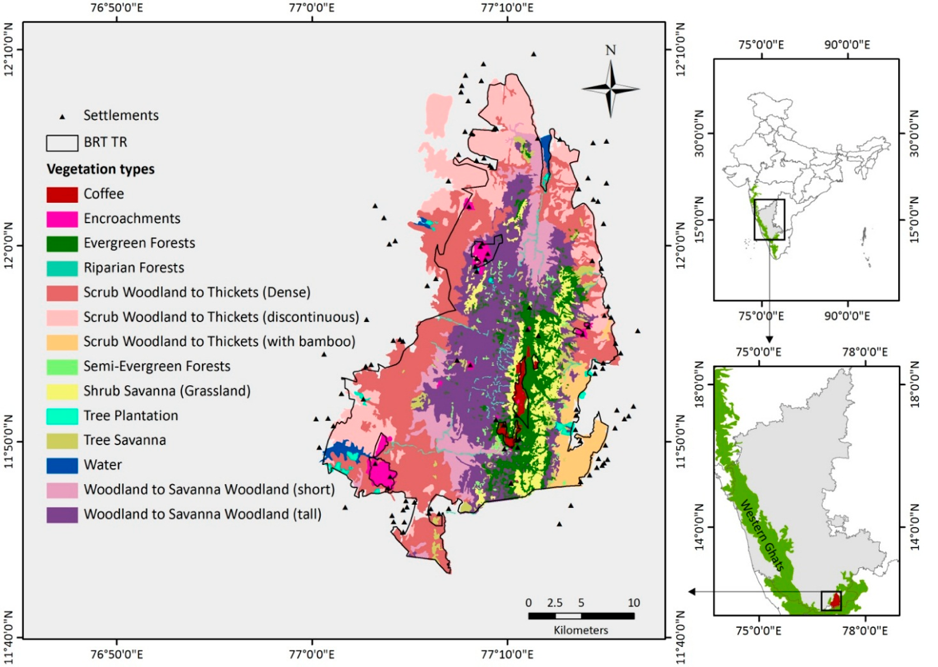

The Soligas have historically inhabited the Biligiri Hills of Karnataka in India for millennia. However, over recent decades, there have been changes in their rights and access to land and forest resources due to evolving policies and land designations that are still based on the country’s colonial past. The Biligiri Hills comprise part of the BRTWS, which was declared a wildlife sanctuary in 1974, covering an area of 540 km2 (Figure 2). In 2011, this wildlife sanctuary was turned into a tiger reserve. The BRTWS is currently home to about 70 tigers, more than 300 elephants and many other animals, such as deer, bison and leopards, among other unique flora and fauna.

Image captions

Image 1

Image 1Soligas village located within the BRTWS in the Western Ghats.

Soligas village located within the BRTWS in the Western Ghats.

Soligas village located within the BRTWS in the Western Ghats.

Figure 2. The BRTWS and Soliga settlements within the region (shown as triangular dots, each representing a ‘Podu’, within the Western Ghats). The upper and lower inset maps on the right-side panel illustrate the extent of the Western Ghats, with the BRTWS (shown as a red area in the lower right panel) (Source: Mallegowda et al. 2015).

Soligas village located within the BRTWS in the Western Ghats

Soligas village located within the BRTWS in the Western Ghats

The Soligas, or Adivasi as called in India (meaning “the original inhabitants of the land”), are an Indigenous tribe believed to be among the first settlers in India. They speak the Dravidian language and practice subsistence living to date.

The Soligas have historically inhabited the Biligiri Hills of Karnataka in India for millennia. However, over recent decades, there have been changes in their rights and access to land and forest resources due to evolving policies and land designations that are still based on the country’s colonial past. The Biligiri Hills comprise part of the BRTWS, which was declared a wildlife sanctuary in 1974, covering an area of 540 km2 (Figure 2). In 2011, this wildlife sanctuary was turned into a tiger reserve. The BRTWS is currently home to about 70 tigers, more than 300 elephants and many other animals, such as deer, bison and leopards, among other unique flora and fauna.

Figure 2. The BRTWS and Soliga settlements within the region (shown as triangular dots, each representing a ‘Podu’, within the Western Ghats). The upper and lower inset maps on the right-side panel illustrate the extent of the Western Ghats, with the BRTWS (shown as a red area in the lower right panel) (Source: Mallegowda et al. 2015).

The Soligas’ coexistence with tigers and elephants

For the outside world, looking at the Western Ghats’ sprawling and sumptuous landscape, the Soligas living with tigers and elephants without any protective measures, such as fences, represents a unique scenario. In the BRTWS, people often encounter wildlife, including tigers, wild boars and elephants. The Soligas have developed methods over the centuries that allow them to coexist with these animals in the reserve.

Living in close proximity to wildlife, the Soligas have reported inherent risks and occasional incidents. According to insights gathered from conversations with elders, on average, one person may die from an encounter with tigers and one or two people from an encounter with elephants and bears every three years. This happens when elephants come in quietly and kill people out of threat. Leopards attack livestock (cattle, goats, chickens etc.) when they come to populated areas.

In relation to such encounters, Soliga elders’ perspectives are unique to the mainstream population:

"We are part of the animals. We have been living with tigers for centuries. We know tiger and elephant behaviours and they know ours. We know their smell and sound and we do not go to those places. Lots of birds ring alarm bells, so we move to different areas. Monkeys and langurs give call sounds. These are life skills. We look after the forest and leave some things for the animals. For example, we do not take all the honey, we leave some there for the animals. We worship tigers, elephants and bison."

Soligas dwelling in the forest

Soligas dwelling in the forest

For the outside world, looking at the Western Ghats’ sprawling and sumptuous landscape, the Soligas living with tigers and elephants without any protective measures, such as fences, represents a unique scenario. In the BRTWS, people often encounter wildlife, including tigers, wild boars and elephants. The Soligas have developed methods over the centuries that allow them to coexist with these animals in the reserve.

Living in close proximity to wildlife, the Soligas have reported inherent risks and occasional incidents. According to insights gathered from conversations with elders, on average, one person may die from an encounter with tigers and one or two people from an encounter with elephants and bears every three years. This happens when elephants come in quietly and kill people out of threat. Leopards attack livestock (cattle, goats, chickens etc.) when they come to populated areas.

In relation to such encounters, Soliga elders’ perspectives are unique to the mainstream population:

"We are part of the animals. We have been living with tigers for centuries. We know tiger and elephant behaviours and they know ours. We know their smell and sound and we do not go to those places. Lots of birds ring alarm bells, so we move to different areas. Monkeys and langurs give call sounds. These are life skills. We look after the forest and leave some things for the animals. For example, we do not take all the honey, we leave some there for the animals. We worship tigers, elephants and bison."

Soligas dwelling in the forest

Soligas dwelling in the forest

In local traditions, the Soligas worship tigers as “Huliverapa”. Wild boars, snakes and other wild animals also belong to different clans. The Soligas have six clans (or “Kulas”) and for each clan, there are specific animals they worship. Hence, overall, the Soligas embrace all wild animals. They also worship trees and stones and have symbiotic relationships with nature that can be seen through the Biligir Hills landscape.

Regarding livestock or human loss, the Soligas do not ask for any compensation from the Government. As the elders describe it: “Animals and people are all part of life. We never ask for any compensation.”

The researchers meeting with Soligas elders

The researchers meeting with Soligas elders

The researchers meeting with Soligas elders

The researchers meeting with Soligas elders

In local traditions, the Soligas worship tigers as “Huliverapa”. Wild boars, snakes and other wild animals also belong to different clans. The Soligas have six clans (or “Kulas”) and for each clan, there are specific animals they worship. Hence, overall, the Soligas embrace all wild animals. They also worship trees and stones and have symbiotic relationships with nature that can be seen through the Biligir Hills landscape.

Regarding livestock or human loss, the Soligas do not ask for any compensation from the Government. As the elders describe it: “Animals and people are all part of life. We never ask for any compensation.”

Recognizing and supporting Adivasi sustainable practices

The coexistence of the Soligas with tigers offers a unique perspective on conservation that prioritizes human exclusion zones like national parks and wildlife sanctuaries and can inspire to reimagine conservation.

We are part of the animals. We have been living with tigers for centuries. We know tiger and elephant behaviours and they know ours.

The Soligas’ ability to live with wildlife over the centuries and sustainably manage the Biligiri Hills region by applying a range of traditional practices (such as recognizing bird voices and flight patterns as indicators of rainfall, the presence of tigers or elephants and worshipping plants and animals to preserve biodiversity) suggests the need to learn from their successful human-wildlife coexistence. Passing on tribal knowledge and strategies (e.g., managing weed and fire, protecting the diversity of plants and understanding animal behaviour and calls etc.) is essential not only for guiding future tribal generations but also for offering insights into forest and wildlife conflict management practices by forest managers and other conservation officials. For example, the management of the Biligiri region by the Soligas is proven to deliver several important ecosystem services for the public, such as fresh and clean air and water to the nearby highly populated areas, sequestration of CO2 and abatement of climate change and prevention of wildfires and soil erosion to protect the cropping areas in the downstream areas. The Soligas’ long-standing harmony with wildlife in the Biligiri Hills underscores the potential benefits of incorporating tribal communities’ traditional knowledge into future conservation strategies.

Photo by Prashanthns on Wikimedia Commons

Photo by Prashanthns on Wikimedia Commons

The way forward

Recognizing and supporting the Soligas’ knowledge and their rights to co-manage the Biligiri Hills might assist the Government in delivering biodiversity protection and climate change mitigation outcomes in a cost-effective manner. This can be achieved by establishing genuine partnerships and collaborations in conservation, leveraging traditional and scientific knowledge systems in decision-making, co-designing incentive schemes such as payments for ecosystem services and providing resources and access to land for the Soligas to actively participate in managing and protecting the Biligiri Hills. Since the Soligas are widely spread across the landscape (Figure 2), engaging people from each Podu (settlement/village) in forest management could be a cost-effective way to help manage the Biligiri Hills in a highly populated country like India. The Soligas’s knowledge would be particularly useful in controlling and managing widely spreading weeds, such as the Lantana camara – an invasive species currently occupying 60% of the area. They could also help sustain wildlife through the provision of food and habitat, supporting people’s subsistence living and providing knowledge and skills to future generations to continue practicing sustainable living in harmony with tigers, elephants and other animals.

The example of the Soligas also encourages us to consider the roles of Indigenous and local knowledge and practices in other Adivasi communities more comprehensively across India in the development of conservation strategies. The wisdom and practices of Indigenous Peoples are deemed to contribute directly or indirectly to 10 out of the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (i.e., 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 13 and 15), from fostering life on land to ensuring sustainable communities. As the engagement of tribal communities in managing forests, controlling wildfires, mitigating climate change, protecting biodiversity and maintaining the flow of ecosystem services benefits the forest departments as well as the wider public, there should be measures in place to reward the good resource stewardship of these communities – for example, by offering economic opportunities through the payment for ecosystem services scheme.

The value of ecosystems like the Biligiri Hills is immeasurable, not just in terms of provisioning, regulating and supporting services they offer but also in the cultural, spiritual and historical richness they represent. The time is ripe for innovative and holistic conservation strategies that simultaneously honour multiple knowledge systems (including Indigenous and local knowledge), promote socioeconomic upliftment of tribal communities and secure the ecological integrity of our world.

Stories like that of the Soligas light our way, reminding us that the key to a thriving planet lies in understanding and fostering the ancient bonds between its people and the rest of nature. Embracing this philosophy of people as part of nature, we can envision a future where nature and humanity flourish side by side, preserving the tapestry of life for generations to come.

Photo by Prashanthns on Wikimedia Commons

Photo by Prashanthns on Wikimedia Commons

The way forward

Recognizing and supporting the Soligas’ knowledge and their rights to co-manage the Biligiri Hills might assist the Government in delivering biodiversity protection and climate change mitigation outcomes in a cost-effective manner. This can be achieved by establishing genuine partnerships and collaborations in conservation, leveraging traditional and scientific knowledge systems in decision-making, co-designing incentive schemes such as payments for ecosystem services and providing resources and access to land for the Soligas to actively participate in managing and protecting the Biligiri Hills. Since the Soligas are widely spread across the landscape (Figure 2), engaging people from each Podu (settlement/village) in forest management could be a cost-effective way to help manage the Biligiri Hills in a highly populated country like India. The Soligas’s knowledge would be particularly useful in controlling and managing widely spreading weeds, such as the Lantana camara – an invasive species currently occupying 60% of the area. They could also help sustain wildlife through the provision of food and habitat, supporting people’s subsistence living and providing knowledge and skills to future generations to continue practicing sustainable living in harmony with tigers, elephants and other animals.

Photo by Prashanthns on Wikimedia Commons

Photo by Prashanthns on Wikimedia Commons

The example of the Soligas also encourages us to consider the roles of Indigenous and local knowledge and practices in other Adivasi communities more comprehensively across India in the development of conservation strategies. The wisdom and practices of Indigenous Peoples are deemed to contribute directly or indirectly to 10 out of the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (i.e., 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 13 and 15), from fostering life on land to ensuring sustainable communities. As the engagement of tribal communities in managing forests, controlling wildfires, mitigating climate change, protecting biodiversity and maintaining the flow of ecosystem services benefits the forest departments as well as the wider public, there should be measures in place to reward the good resource stewardship of these communities – for example, by offering economic opportunities through the payment for ecosystem services scheme.

The value of ecosystems like the Biligiri Hills is immeasurable, not just in terms of provisioning, regulating and supporting services they offer but also in the cultural, spiritual and historical richness they represent. The time is ripe for innovative and holistic conservation strategies that simultaneously honour multiple knowledge systems (including Indigenous and local knowledge), promote socioeconomic upliftment of tribal communities and secure the ecological integrity of our world.

Stories like that of the Soligas light our way, reminding us that the key to a thriving planet lies in understanding and fostering the ancient bonds between its people and the rest of nature. Embracing this philosophy of people as part of nature, we can envision a future where nature and humanity flourish side by side, preserving the tapestry of life for generations to come.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the Soliga elders for their input and for sharing knowledge and concerns related to living in the Biligiri Hills. During this research, the support and help offered by the local staff of the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment are highly acknowledged.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the Soliga elders for their input and for sharing knowledge and concerns related to living in the Biligiri Hills. During this research, the support and help offered by the local staff of the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment are highly acknowledged.